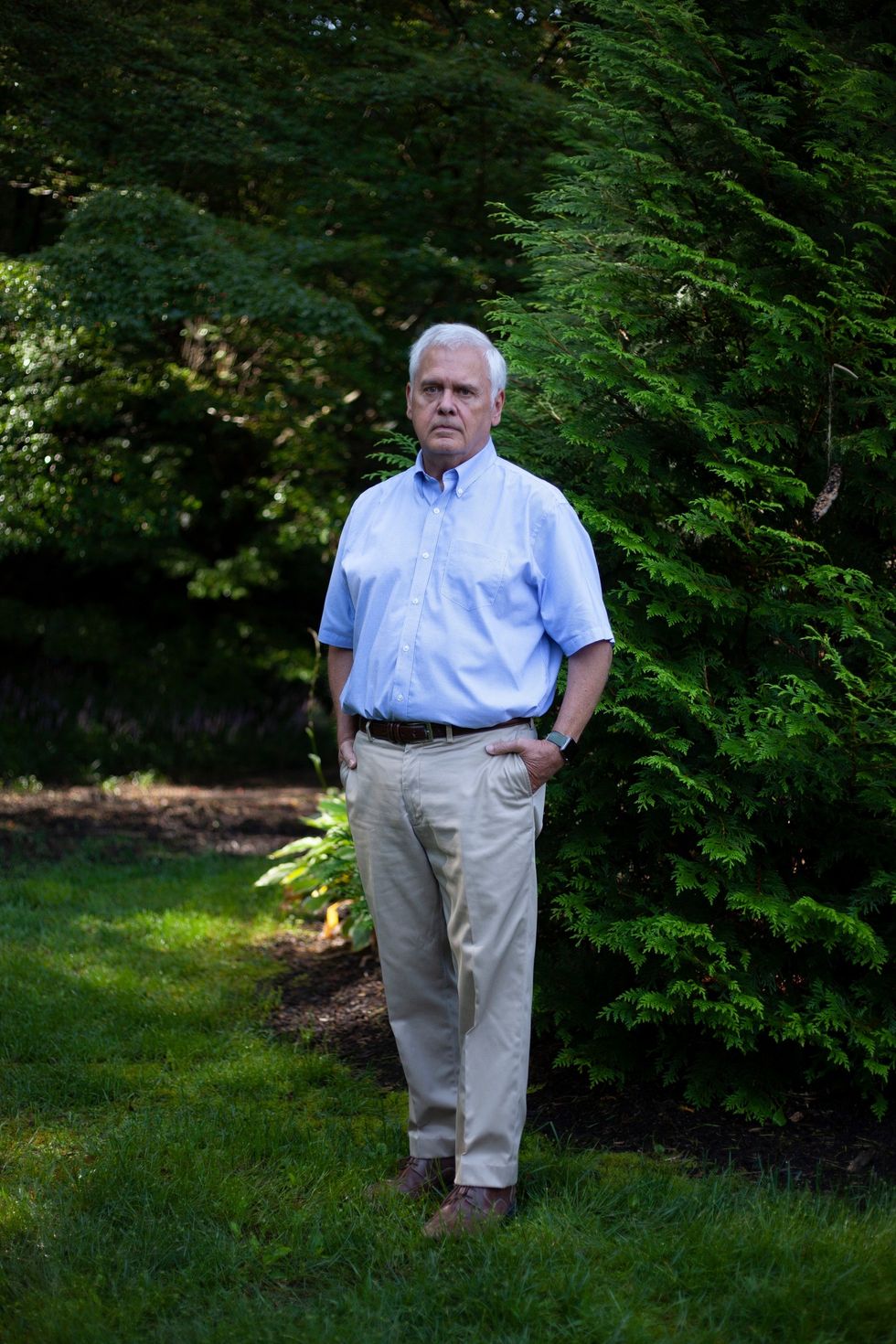

Mike Hawkins, the Republican chairman of the Transylvania County Board of Commissioners, in North Carolina, was on vacation last summer when he saw clips from Donald Trump's speech to cheering supporters at East Carolina University, in Greenville. Earlier that week, Trump had aimed tweets at four prominent Democratic members of Congress, all women of color, suggesting that they should "go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came." Never mind that three of the four had been born in the United States, and the fourth, Ilhan Omar, had left Somalia as a refugee when she was a young girl. At East Carolina, Trump lit into Omar, prompting the crowd to chant "Send her back!" He attacked the four representatives as "hate-filled extremists" and defended his tweets, saying, "You know, they don't love our country."

That was enough for Hawkins. And so, at the next commission meeting in Brevard, population eight thousand, Hawkins, who is white, called out the President. "What happened at E.C.U. can only be described as racist," he said. "It's important that people identify hate for what it is—a poison to our state and to our country. And I wanted to say in a very public way that for whatever time I have remaining as an elected official, I will oppose this poison every way I can." When he finished, two other white Republicans on the commission, Page Ives Lemel and W. David Guice, the state's former commissioner of adult correction and juvenile justice, offered words of support.

Five months later, all three quit the Republican Party. Between them, they had won twenty elections as Republicans, yet they had grown disenchanted not just with Trump but with the G.O.P. When they looked at the Party's leadership in North Carolina and across the country, they said, they saw too many officials who catered to narrow constituencies, dismissed inconvenient truths, ignored the rule of law, and undermined the idea that government exists to serve the common good. "Where did we get so far off the path of believing the facts and doing the right thing?" Lemel asked, when I visited her at the summer camp that she owns near the Pisgah National Forest. "Where did we, as a country, lose sight of doing right for right's sake?"

In a year of rising discontent with Trump, an increasing number of Republicans are going public with their disdain for the President—and, in many cases, for the politicians and operatives who have cheered him, indulged him, or stood by without an opposing word during his Administration. These dissenters' histories vary, as do their tactics, but they are united in the goal of denying him a second term. Groups such as the Lincoln Project and Republican Voters Against Trump are delivering dozens of attack videos, often responding within hours to the latest Trump calumny. Republicans opposing Trump were given prime-time slots during last week's Democratic National Convention. Colin Powell, the former Secretary of State, said that Trump is "doing everything in his power" to divide the country. The former Ohio governor John Kasich spoke, as did Meg Whitman, the onetime California gubernatorial candidate, who said that Trump "has no clue how to run a business, let alone an economy." On Monday, twenty-seven Republicans who once served in Congress, including the former senators Jeff Flake and John Warner, endorsed Biden.

As the scaled-back Republican National Convention begins in Charlotte, on Monday, Robert Orr, a former North Carolina State Supreme Court justice, is working with a group called Stand Up Republic and its partners to peel G.O.P. voters away from the President. Operating from a downtown hotel for the four nights of the Convention, they will broadcast speeches from dozens of well-known Republicans who oppose Trump, as part of a virtual gathering called the Convention on Founding Principles.

Speaking about the Trump campaign, Orr said, "We just can't let them come into North Carolina and have four days of B.S. and lies. We need to have some sort of counter-message." The event will feature the former New Jersey governor Christine Todd Whitman, and such Trump critics as the former F.B.I. director James Comey, the former C.I.A. director Michael Hayden, and the diplomat Brett McGurk. Will it matter? In the 2016 election, when more than a hundred and thirty-five million people cast ballots, a shift of thirty-nine thousand voters from Trump to Hillary Clinton across three states—Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania—would have given her the election.

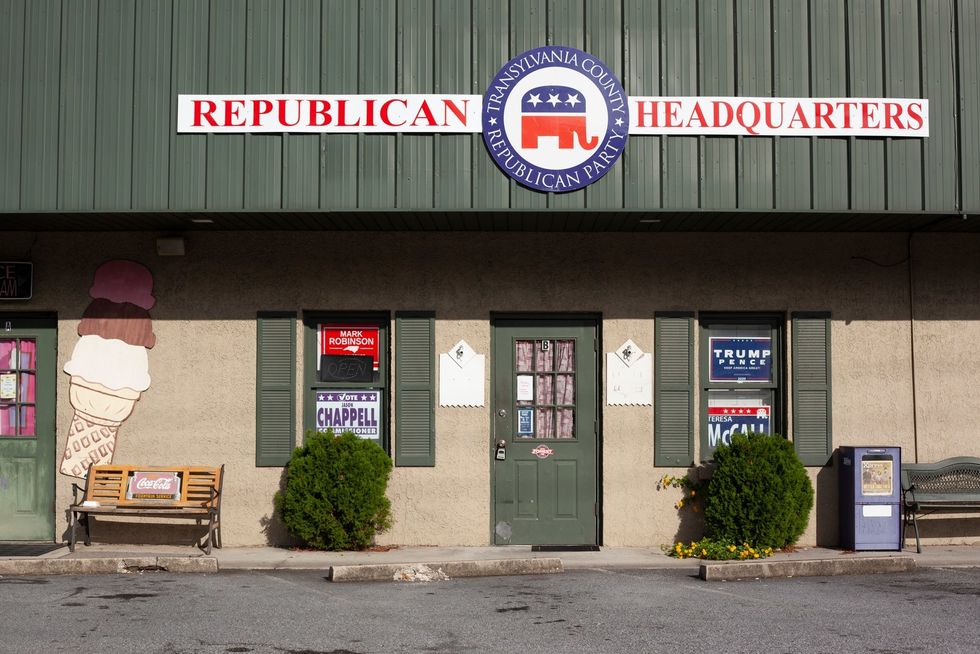

In Transylvania County, which is part of the House district once held by Trump's chief of staff, Mark Meadows, it took gumption for the three commissioners to oppose the President and ditch the G.O.P. They made their move in December, before the arrival of covid-19, and before polls showed Trump losing support almost everywhere. Hawkins and Lemel will both be on the ballot in November, facing Republican challengers who have aligned themselves with Trump. "Page and I were talking the other day, and we said we were glad we did what we did, when we did it. We are ahead of the curve," Hawkins said. "We know a lot of people would say, 'Big deal, they're just small-town.' But in many ways, that makes it harder. We see people and hear from people every day, and we really exposed ourselves through what we did."

Hawkins, who is sixty-two, dates his frustration with the direction of the Republican Party to 2012, when Tea Party Republicans launched a campaign against Agenda 21, a nonbinding United Nations resolution that advocated for sustainable development. The measure had been signed in 1992 by President George H. W. Bush and the leaders of more than a hundred and seventy-seven other countries; twenty years later, it was attacked by the Republican National Committee, which warned that it was a "destructive and insidious" policy that would lead to a "socialist/communist redistribution of wealth." Conservative activists in western North Carolina invoked the spectre of Agenda 21 and used the same logic to attack a local agreement called GroWNC, a voluntary planning effort that was designed to improve coöperation among five neighboring counties. Meadows, a Tea Party favorite and first-time congressional candidate, warned that, just as Agenda 21 supposedly threatened U.S. sovereignty, regional arrangements posed "a threat to our freedoms and to our property rights," and must not be allowed to usurp local authority.

To Hawkins, a business owner and good-government moderate, the criticism was claptrap. Transylvania County and its neighbors simply wanted to work together, try new ideas, and maybe find some efficiencies on such issues as transportation, energy, health care, and the environment. No one's authority would be usurped. But the fuss caused Transylvania to withdraw from the partnership; Hawkins believes that the county is still suffering from the decision. He became a Republican because he admired pragmatic local politicians who thought first of the community, but he noticed that they were fading from the scene as hard-liners ascended. In North Carolina, Party leaders refused to expand the Medicaid provisions of the Affordable Care Act, a missed opportunity to provide health care to working-class residents. Fed up, Hawkins stopped going to local Republican gatherings where, he said, the messaging was not only "harmful" but "nutty."

Lemel joined Hawkins on the commission after the 2012 election, and Guice followed six years later, each earning a yearly salary of twelve thousand four hundred and four dollars for their service. Lemel's father had formerly chaired the commission, and been elected to the state legislature. Guice had previously served on the commission, before being elected to two terms in the state legislature, where he worked across the aisle to pass criminal-justice reform. Lemel said that, as they watched Trump in action, "we were mortified. All three of us come from a very deep history of true conservative thinking and good moral integrity and lots of strong values in our families." They saw little of that in the President or the national Republican leadership, whether it was Trump's relentlessly demeaning behavior or the G.O.P. sponsorship of tax cuts that would never pay for themselves and disproportionately benefitted the wealthy. Lemel, whose focus is on early education and mental health, said, "It's such a struggle—wanting to do what I feel is really right in my heart and feeling left behind by a Party that's become overly federalized, and overly loyal to a man who, in my personal opinion, doesn't deserve it."

I spoke with Lemel on a shaded porch at Keystone Camp, a private girls' sleepaway camp tucked into a wooded hillside in Brevard. Founded in 1916, the camp is open for business this summer, but with fewer girls, to allow for social distancing. Lemel, who is fifty-eight, lives year-round at the camp with her husband, a doctor. She has a habit of collecting sayings, many of them about the perpetual challenges faced by women, including "a whole list of quotes that probably infuriate my husband." She said that, these days, "we joke a lot around here about mansplaining." One of the speeches she most admires is Margaret Chase Smith's Declaration of Conscience, from 1950, when the freshman Republican senator attacked the anti-Communist crusade led by Senator Joseph McCarthy. Smith warned of "totalitarian techniques" and said that Republicans should not be allowed to triumph through "Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry, and Smear."

Lemel, who stuffed envelopes for Gerald Ford's Presidential campaign years before she was eligible to vote, has trouble fathoming that Trump, with his bullying and his bluster, has captured the Republican Party. And then there are elected officials, men and women she once respected, who are now "playing petty politics for self-preservation." Many episodes have fuelled her dismay, including the Republican-led Senate's refusal to consider the nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court in 2016. She sees damage inflicted by the Administration's rudderless foreign policy, calling it "humiliating." Then there is the bigotry. "We can't continue to think that being over sixty and being white," she said, "entitles you to be better than everybody else." And then there's the recent array of measures designed to suppress the vote. "The fact that the President of the United States can vote absentee and he's not willing to let other people to do that? Oh, grow up!"

Brevard is a small town. When two of the commissioners ran into one another, they would shake their heads at the latest remark or policy announcement from the White House. Little of it made sense. "I'd also say it was the daily dishonesty and utter lack of integrity that we saw from the leaders of the Party," Hawkins said. "It was just a drip-drip that became unbearable." Last December 4th, after sharing their decision with a few close friends and colleagues, they issued a statement saying that they were leaving the G.O.P. Guice said that some friends warned him that he was ruining his career. Nearly sixty-five years old, he was unconcerned about any potential electoral consequences, but he did have his legacy in mind, and that proved to be a deciding factor. "To me, it was based on principle, on my belief system," he said. "I want my children and my grandchildren to know where I stand."

Bob Orr, the former State Supreme Court justice and onetime chairman of the Buncombe County Republican Party, would like to see more local leaders publicly oppose the President. With recent polls showing Joe Biden ahead by a narrow margin in a state that Trump won in 2016, Orr has been urging anti-Trump Republicans to speak out and give cover to conservatives who reluctantly chose Trump last time, or who have soured on him since. Orr is working with Stand Up Republic, an organization headed by Evan McMullin and Mindy Finn, Republicans who ran for the White House four years ago on an independent ticket that was more political statement than serious candidacy. Now they are recruiting Republicans to vote for Biden, or at least not to vote for Trump, in North Carolina and Arizona, two battleground states that the Democrats hope to win. Finn told me that their target is "soft Trump supporters," including suburban women, veterans and military voters, and white Christian evangelicals, especially younger ones. It's a difficult task, she said, "just because of the muscle memory when you're a Republican who's always voted for a Republican. It's extremely emotional for people to step outside their tribe and party. They need somebody they know, or if they don't know them personally, they have a shared affinity."

Orr made clear his opposition to Trump early, when he went to the 2016 Republican National Convention as a John Kasich delegate and criticized Trump as "dangerous" and "unqualified." He regularly hears from Republicans who say that they have had enough, but his project is not universally welcomed. We met on a Saturday morning in Burnsville, near a cabin he owns. After we had spoken, he proposed lunch at the Country Club of Asheville. We arrived on the back deck at the same time as a group of men, who were travelling by private plane to play three courses in three states in three days. As we sat down, one of the men joked that Orr was making some good Republicans angry, and called out to me, "I hope you've got a pistol if you're hanging out with Bob Orr!"

Orr traces his Republican roots to his great-grandfather, Robert F. Orr, who fought on the Union side during the Civil War after first being pressed into the Confederate Army. He is buried in the Beulah Baptist Church Cemetery, south of Asheville, overlooking a lake and a winding, two-lane country road. Beneath his name, the stone marker reads, "A plain man true to his Country, Church and family." Orr thinks of his ancestor's brave choices as he makes his own decisions. As he scanned the surrounding landscape, he said, "This is Republican country." He didn't mean it as a compliment. As we drove, we passed a yard sign that said, "Stop Socialism. Trump 2020."

The effort of Orr and friends in North Carolina is distinctly "nuts and bolts," as he puts it, unlike the high-profile, thumb-in-your-eye social-media work of the Lincoln Project. One local recruit is Charles Jeter, a Republican former state legislator, who wrote in a June newspaper column that he is "angry that the party I love has so easily and completely turned over its principles in the quest for power." Another is Penny Slade-Sawyer, the former U.S. Assistant Surgeon General and North Carolina director of public health, who told me that she believes that Trump's poor leadership during the coronavirus pandemic has "cost people their health, their wealth, and some of them their lives." She added, "I'm no liberal, but I think the Republican Party has gone off track." Slade-Sawyer is speaking out where she can, including at the counter-convention in Charlotte. "I'm an old lady and I'm going to say exactly what I think," she said. "Maybe a few people will listen."

Back in Transylvania County, Lemel and Hawkins have reason to be concerned about holding on to their county-commissioner seats. The local Republican Party ran a full-page advertisement in the Transylvania Times last month endorsing the Republicans who are challenging them. Under the heading "We Are Trump Conservatives Supporting the 'Thin Blue Line,' " the G.O.P. candidates wrote of police under siege and mobs "taking a page from the Marxist revolution playbook." In cities run by Democrats, they declared, "police departments are being significantly defunded or abolished altogether." The fact that the argument bears no relation to rural Transylvania County neatly encapsulates the conditions that drove the three commissioners from the G.O.P.

Lemel told me that she was treated like "the lowest of the low" in her community after she resigned from the Party, and that a friend of her father's asked disdainfully, "How could you?" The reaction bothered her, but she has no intention of revisiting her decision, which raises questions about the future of the G.O.P. History and logic suggest that the Party must pivot toward the center to remain viable in the years ahead. Whether it does so, and when, remains entirely unclear. One thing that's clear is that Lemel will not be supporting Trump, and his campaign now knows it. When a Trump 2020 staff member contacted her in late July, she gave a lengthy explanation of her reasoning and concluded her response by saying, "I will not support Donald Trump, as I feel he has failed as a conservative, principled leader." Lemel will be voting for Joe Biden.

focussing on politics. He teaches at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism and is the author of "Michelle Obama: A Life."

###

August 24, 2020

Voices4America Post Script. Tonight, when the shards of the Republican Party crash on the ground, transmuting into #TrumpCult, it is good to know that there are good people defecting. I posted earlier about 24 former GOP Congresspeople, but these are grassroots GOP folks. Read this! Did you know there is a counter RNC, Convention on Founding Principles? Share this!

FYI, North Carolina allows any voter to request a ballot by mail. You can also vote in person. North Carolina offers early voting starting on October 15. #BidenHarris2020