During the colonial era, it was customary for masters to grant "freedom dues" to indentured servants who had completed their fixed term of service. They were given land at times but at the very least tools and livestock to help begin their new lives in freedom. When former slaves demanded land after the Civil War, they were harking back to this longtime custom, which the rest of the country (with the exception of the abolitionists) had long forgotten. Since the Reconstruction era, the reneged-upon promise of repara-tions—recompense to African-Americans for centuries of enslave-ment and racial oppression—has continued to fester like an open sore on the nation's body politic.

Many Americans dismiss the idea of reparations as economically impractical, legally impossible and politically inflammatory. In the 20th century, however, several countries—most prominently postwar Germany but also the U.S.—have offered significant reparations for past atrocities. Though the issue of reparations for slavery never really died down, especially among African-Americans, the cause was given new life in 2014 by the author Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose landmark essay "The Case for Reparations" in the Atlantic has shaped the current debate on redress not just for enslavement but for a century of systematic racial discrimination sanctioned by the state.

The earliest calls for reparations came from the enslaved and those who objected to the permanent and hereditary nature of racial slavery in the English colonies. George Fox, the founder of the Quaker faith, called for freeing slaves after a term of service and, as early as 1672, argued that they should be compensated for their labor and not sent off "empty handed." In the 18th century, the Quakers became the first Christian denomination to ban slave-trading and slaveholding among its mem-bers, and they were overrepresented in the Revolutionary-era abolition movement. Many heeded Fox's injunction and gave their freed slaves material support for their new lives.

In the New England colonies, which became the hotbed of abolitionism in the 19th century, slaves led the way in demanding redress from the government. An extraordinary 1774 petition by a group of black slaves addressed to the Massachusetts General Court (the state assembly) declared, "Give and grant to us some part of unimproved land, belonging to the province, for a settlement."

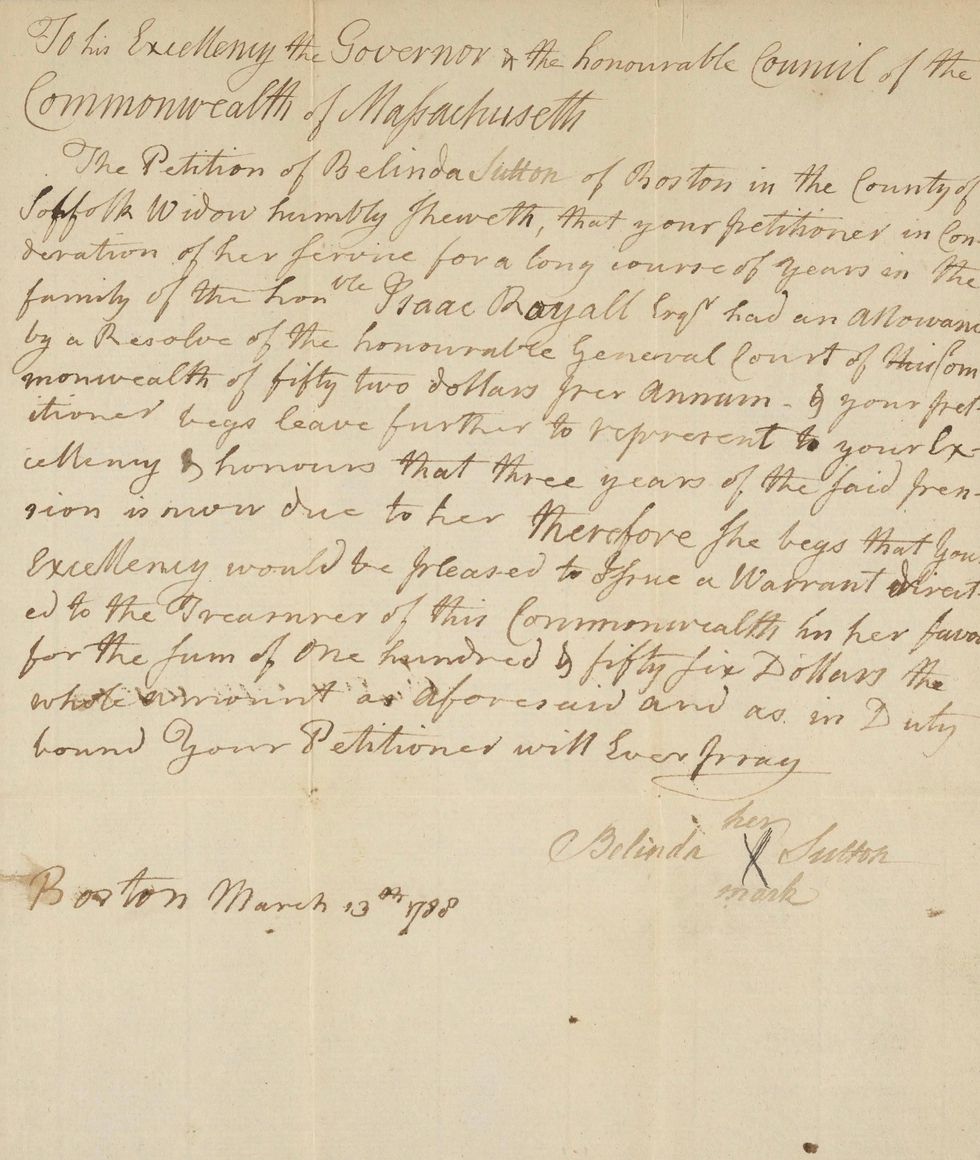

In 1783, a formerly enslaved woman from Massachusetts, Belinda Sutton, became the first to win reparations for her years in bondage. A striking petition on her behalf to the Massachusetts General Court recounted her abduction from Africa and argued that "by the laws of the land" she had been "denied the enjoyment of that immense wealth, a part whereof has been accumulated by her own industry, and the whole augmented by her servitude." The court granted her petition, in part because her enslaver, Isaac Royall Jr., was a Tory who had resisted American independence. In 1787, Sutton petitioned again and won a pension from his estate. (Royall, her enslaver, made a substantial bequest to Harvard Law School. After student protests over this slavehold-ing connection, the school removed his crest from its seal in 2016.)

Though many universities in the Anglo-American world have recently explored their history of ill-gotten wealth from slave trading and slavery, only a handful of predominantly religious institutions have moved toward reparations. The best-known example is Georgetown University, where Jesuits sold 272 slaves in 1838 to save their college. Not only did Georgetown offer a formal apology, it also tracked down the slaves' descendants to offer them admission. Recently, the university's students voted overwhelmingly for an increase in fees to pay repara-tions, and a large endowment has been set up for descendants.

Religious institutions have often taken the lead in reparations for slavery, seeing it as fundamentally a moral question as well as an economic one. Last year, the sisters of the Society of the Sacred Heart, an international Catholic group that owned slaves in Missouri and Louisiana, created a reparations fund. Just this month, the Virginia Theological Seminary, an Episco-palian institution that still has buildings today built by slaves, created a $1.7 million reparations fund for descendants of the enslaved.

In her important 2017 book "Reparations for Slavery and the Slave Trade," the Howard University historian Ana Lucia Araujo shows that attempts to repair past harms have ranged from formal apologies to economic indemnification to compensatory programs. In the U.K., for instance, Glasgow University, a center of 19th-century abolitionist activism, recently created a reparations fund of 20 million pounds after acknowledging that the university had benefited from Scottish slave traders to the tune of more than $100 million (in the dollars of the day). In 2017, All Souls College, Oxford, instituted a fellowship for a student from the West Indies and paid 100,000 pounds to Codrington College in Barbados in partial redress for the 10,000 pounds (worth millions today) that All Souls received to build its library from Christopher Codrington, who had made his fortune in slavery.

In the U.S., several institutions of higher learning preceded Georgetown in considering their past connections with enslavement. In 2003, President Ruth Simmons of Brown University first commissioned a report on the school's involvement in slavery and the slave trade, which led Brown to take several measures, including a $10 million endowment to educate disadvantaged children in Provi-dence, R.I., rendering technical assistance to historically black colleges and universities, and funding research on slavery and racial justice. Since then, other universities—including Columbia, Emory, Harvard, Princeton and the University of Virginia—have explored their own institutional histories of benefiting from cen-turies of human misery, although none of them has offered reparations.

Ironically, in considering emancipation, governments were often preoccupied with compensat-ing slaveholders for their loss of human property rather than the enslaved for their stolen labor, bodies and lives. British emancipa-tion compensated slaveholders and reduced freed people to apprentice-ship, a liminal state between slavery and freedom. In 1862, when slavery was abolished in the District of Columbia, slaveholders rather than slaves received compensation.

But the Union victory in 1865 brought an end to this practice, which abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison, who wanted redress for the slaves themselves, had long protested. The destruction of slavery during and after the Civil War resulted in the largest confiscation of private property by the state in American history, with the freeing of nearly four million slaves valued at around $3 billion at the time.

Perhaps the most famous episode in the history of reparations came in 1865, when Union Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's famous Field Orders No. 15 divided abandoned and confiscated planta-tions in low-country South Carolina and Georgia into 40-acre lots for newly freed people and gave each of them a mule. The news of "Forty Acres and a Mule" spread like wildfire among the formerly enslaved—only to be dashed within a few months when Andrew Johnson, who became president after Abraham Lincoln's assassination, returned the Sherman land grants and other lands distributed by the federal Freedmen's Bureau to former slave-owning planters.

The sense of betrayal lingered among African-Americans, especially after the overthrow of Reconstruction and the failure to rectify the cruelties of racism. Freed people in the post-bellum South were soon disenfranchised, segregated and subjected to racial terror, debt peonage and semi-servitude in the notorious system of "convict leasing," all of which made a mockery of black freedom. When Spike Lee started making movies on racial themes in the 1980s, he pointedly named his production company 40 Acres and a Mule.

After Reconstruction, former slaves took the lead in demanding compensation. A significant step came in 1896, when Callie House and Isaiah Dickerson founded the first national organization for repara-tions, known as the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association. Despite government persecution, the association marked the start of a reparations movement among African-Americans that has continued until today.

In 1987, in the wake of the civil-rights movement, black groups and leaders including James Forman founded the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America, or N'COBRA. Its current incarnations include grass roots organizations such as the Unpaid Labor Project and the Movement for Black Lives, which call for reparations not just for enslavement but also for its lingering legacies: racial "redlining" for insurance and financing, mass incarceration, racism in law enforcement, and the yawning gaps between blacks and whites in wealth, health, education and opportunity.

It has proven easier for governments to pay reparations for particular historic wrongs than for centuries of what Mr. Coates has called the "quiet plunder" of black labor and wealth. Perhaps the most successful case is West Germany's 1953 agreement to pay some $845 million (in the dollars of the day) to the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany and the newly founded state of Israel as reparations for the Holocaust. (German history also offers a case when reparations failed: Making Germany pay enormous reparations after World War I helped pave the way to World War II.)

The U.S. government also formally apologized and paid reparations to Japanese American citizens wrongfully interned in camps during World War II—to the tune of $20,000 each—with the passage of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. More recently, the city of Chicago agreed to pay several million dollars in reparations to victims of systematic police brutality and torture.

In 2009, the U.S. Congress formally apologized for slavery, but public officials often dismiss the demand for reparations as utopian or a prescription for a legal quag-mire. Nor has the U.S. seriously considered convening a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as South Africa did after the fall of apartheid, to grapple with the legacies of enslavement. As the moral philosopher Susan Neiman notes in her recent book "Learning From the Germans," while post-Nazi-era Germans have frankly acknowledged the evil that their country had done, unreconstructed Neo-Confederates in America still peddle the mythol-ogy of the "Lost Cause" and offer what Frederick Douglass called "eulogies of the South and of the traitors." To make amends for historical wrongs, one must first genuinely acknowledge the harms done.

As historians of slavery continue to demonstrate the extent to which the economies of the Americas and Europe grew on the backs of black people, a "fully loaded cost accounting" of slavery, in the historian Nell Irvin Painter's words, might seem too immense. The scale of the challenge has certainly paralyzed any substantial redress for enslavement and its brutal aftermath. Proposals for a Marshall Plan for America's inner cities have been stillborn. In 1989, Rep. John Conyers introduced a bill to establish a commis-sion to study reparations, which languished despite his reintroducing it year after year.

In 2016, President Barack Obama showed himself highly attuned to the pragmatic difficulties of pursuing reparations in the face of strong opposition. As he told Mr. Coates, "The bottom line is that it's hard to find a model in which you can practically administer and sustain political support for those kinds of efforts." Critics of reparations usually look past the enduring deleterious effects of slavery and its brutal aftermath, focusing instead on slavery's end in the 19th century. Last June, right before a House hearing on the issue, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell rejected the idea of present-day compensation: "I don't think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago, for whom none of us currently living are responsible, is a good idea."

Still, activists, journalists and historians have kept the debate alive, and the push for reparations has recently achieved a new visibility in national politics. In Mr. Coates's congressional testimony this June, he said that African-Americans were still suffering from the aftermath of slavery and urged lawmakers to "reject fair-weather patriotism, to say that this nation is both its credits and debits." As the 2020 campaign heats up, the willingness of several Democratic presidential candidates, including Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Kamala Harris, to consider at least some sort of remedy for slavery and ongoing racism have put reparations back on the national agenda.

Whatever specific shape reparations may eventually take, it is a national moral debt that is long overdue. The Constitution's 13th Amendment abolished slavery in 1865, but Congress is also empowered, as the Supreme Court has ruled, to eliminate the "badges and incidents of slavery" under whose historical weight so many of the nation's African-American citizens have groaned for too long.

—Prof. Sinha is the James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecti-cut. Her books include "The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition" (Yale University Press) and "The Counter-revolution of Slavery" (University of North Carolina Press).

Wall Street Journal. September 20, 2019

###

September 22, 2019

Voices4America Post Script. Reparations for slavery - a topic which is top of mind and clear for some, obscure, confusing or rejected by others. We need facts if we are to find a way to make America morally whole. This article provides a strong overview. Share it! #Reparations