Monuments and memorials bearing the names of men who fought to preserve slavery and uphold white supremacy are facing a reckoning, as demonstrations against police brutality have erupted across the country in response to the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer.

The protests have also reignited a debate within the military community over 10 Army bases named after Confederate leaders, which as recently as February the service said it had no intention of changing, according to the military website Task & Purpose.

The service backtracked on that position, as a Pentagon official said Monday that Secretary of Defense Mark P. Esper and Secretary of the Army Ryan D. McCarthy were "open to a bipartisan discussion on the topic" of removing Confederate names from the bases. The announcement, first reported by Politico, came as each of the services have started to contend with many longstanding practices and allegations of racial bias that have gone unaddressed.

The Pentagon official said Esper and McCarthy wanted Congress, the White House and other government officials to weigh in, according to CNN, shifting the responsibility onto lawmakers.

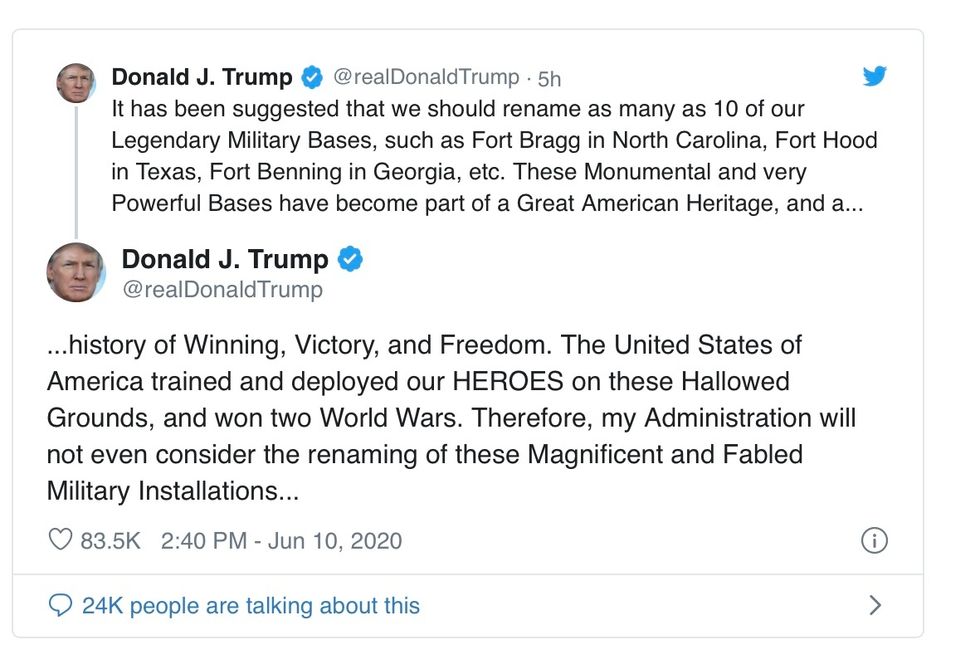

President Trump on Wednesday was quick to shut down any bipartisan discussions, tweeting, "my Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations."

What is the process for renaming bases?

The decision to name (or rename) installations falls to the assistant secretary of the Army for manpower and reserve affairs — an office currently held by retired Army officer Casey Wardynski. In the mid-2000s, Wardynski developed a video game called "America's Army" while serving on the faculty at West Point. Army guidance directs that installation names be relevant to their surrounding areas.

The Army had no comment on the president's declaration when reached by phone Wednesday afternoon. There is no requirement for politicians or the White House to approve Army base name changes, though it's unclear if the service will still consider the move following the president's tweets.

Where do military bases get their names?

Since the Revolutionary War, military bases have been named for commanders, high-ranking officers and even the engineers who supervised their construction. Until World War I, base names often, but not always, reflected local influences or historically significant soldiers local to the area.

On April 11, 1861, Brig. Gen. Pierre G.T. Beauregard, commander of Confederate forces in the Charleston area, demanded that Maj. Robert Anderson of the Union Army surrender his command at Fort Sumter in South Carolina. Anderson refused. Beauregard opened fire. And the Civil War ensued.

Today, Beauregard has a U.S. Army base in Louisiana named after him. Anderson does not.

Beauregard was not alone in receiving such a high honor as a traitor to the United States. At least nine other major Army installations are named for generals who led Confederate troops — a practice the Army has defended for years based on the assertion that they have "a significant place in our military history," as one Army official recently said.

Among the former states of the Confederacy, Texas, Alabama, Georgia, and North Carolina each have one Army base named for a Confederate general, according to a 2017 Congressional Research Service report. Louisiana and Georgia have two each. And Virginia, which served as the seat of government for the Confederacy, has three such installations.

Most of these bases were established during World War I as "camps" and periodically shuttered between wars. In World War II, many of them were formally established as "forts" with their original names intact. But in at least one instance, a training area within a fort was named for a Confederate as recently as 1979 — Wilcox Camp, named for Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox, within the confines of Fort A.P. Hill in Virginia, itself named for a Confederate general.

Why haven't the names been changed already?

The NAACP has long advocated for changing the names of military bases honoring Confederate soldiers, arguing that the battle flag glorifies "treason and a hateful history of white supremacy and black subjugation."

The call to remove Confederate leaders' names surfaces every time the continuing issues of race and the grim legacy of the Civil War and slavery in the United States are brought to light by current events. It was discussed following the mass shooting of nine black worshipers in Charleston, S.C., by avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof in 2015. Roof documented his fetishization of the Confederate flag in a blog before carrying out the attack, and also embraced the flags of Apartheid-era South Africa and the white-controlled nation of Rhodesia, now known as Zimbabwe.

After white supremacists marched on Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017, ostensibly to protest the proposed removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee, the idea of renaming Army bases was again floated by academics and pundits alike. Military leaders publicly denounced racism at the time, but Gen. Mark A. Milley, then the Army chief of staff, elected not to pursue renaming bases. Milley has since become chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He received criticism last week for accompanying President Trump from the White House to a church in his camouflage uniform on June 1, moments after the area had been cleared of peaceful protests by security forces using tear gas.

Are the other services taking other steps to address Confederate imagery and symbolism?

The U.S. Navy has in the past commissioned several warships bearing the names of Confederate leaders — including a nuclear missile submarine named for Robert E. Lee that joined the fleet in 1960 and served until 1983. Today, the service has a cruiser named for the Battle of Chancellorsville — which in an official Navy history is noted as a "great victory" for the Confederacy. The U.S.S. Chancellorsville is homeported in Japan.

In 2017, the Navy issued a directive acknowledging the bitterly divisive nature of Confederate symbology and said leaders "should not connect the Navy to the Confederate battle flag in a way that undermines the Navy's message of inclusiveness." On Tuesday, Navy leadership announced the service would soon ban the Confederate battle flag from all public spaces on Navy installations, ships and aircraft. The announcement came just days after a retired Navy captain resignedfrom the board of the U.S. Naval Academy's alumni association for using racist slurs on social media.

On Friday, Gen. David H. Berger banned public displays of the Confederate battle flag at all Marine Corps installations, to include paraphernalia such as mugs, posters and bumper stickers. "Anything that divides us, anything that threatens team cohesion, must be addressed head-on," Berger said. Military.com reportedTuesday that the Army is considering a similar policy.

The Air Force, which formally became a separate branch of the armed forces after World War II, does not have any facilities named after Confederates, according to the Congressional Research Service. Air Force policy requires that any installations named for former members can only consider persons who have "records of outstanding and honorable service."

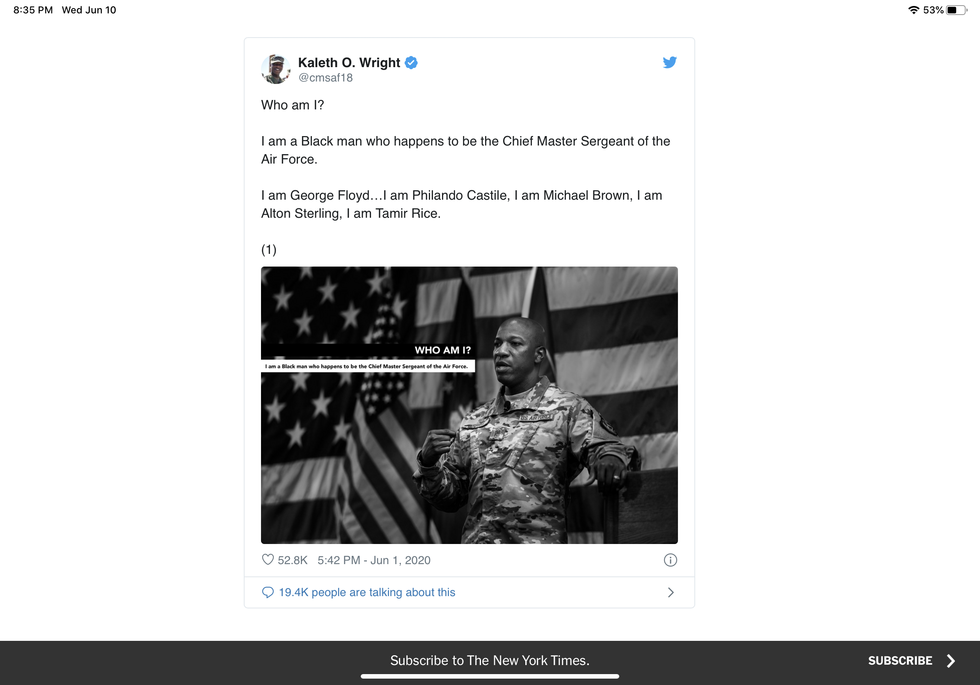

Last week, the Air Force's senior enlisted member, Chief Master Sgt. Kaleth O. Wright, became the first senior military leader to speak publicly against police brutality in the wake of George Floyd's murder.

Wright, who is black, will be joined at the top of the service's leadership by Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., who was confirmed Tuesday by a unanimous vote in the Senate to serve as Air Force chief of staff. Brown is the first black service chief in American history.

If the Army renamed the bases, who would they name them after?

On Twitter, the military community took to offering suggestions for soldiers for whom bases could be renamed. Many proposed that Fort Benning in Georgia — whose namesake is Confederate general Henry Lewis Benning — be renamed for Sgt. First Class Alwyn Cashe, a black soldier and Georgia native who died in 2005 after his Bradley Fighting Vehicle hit a roadside bomb in Iraq and erupted in flames. Cashe returned to the vehicle three times, while he himself was on fire, to rescue his men who were trapped inside. Cashe pulled six soldiers from the vehicle, and despite the second and third-degrees that covered most of his body, he refused to be medevaced until everyone else was out. Three weeks after the attack, Cashe succumbed to his wounds. He was posthumously awarded the Silver Star.

Army Master Sgt. Roy P. Benavidez's name has been suggested as a replacement for Fort Hood in Killeen, Tex., one of the largest U.S. military installations in the world, named after Confederate officer John Bell Hood (who is absent from Fort Hood's official history page). Benavidez received the Medal of Honor for extraordinary valor above and beyond the call of duty as a Special Forces soldier in Cambodia in 1968. The League of United Latin American Citizens, a Texas-based advocacy group, has been advocating for the name change since 2019, according to The Washington Post. So badly wounded after a battle in which he rescued eight soldiers, Benavidez was briefly thought dead. "The real heroes are the ones who gave their lives for their country," Benavidez once said. "I don't like to be called a hero. I just did what I was trained to do."

New York Times, June 10, 2020

###

June 11, 2020

Voices4America Post Script. As Nancy Pelosi said, urging the removal of 11 statues of Confederate soldiers and officials in our Capital, “these statues pay homage to hate, not heritage.”

So too do the Confederate names on our military bases.

The Pentagon is willing to remove these names. Trump, a provocateur and racist, tweeted, "My Administration will not even consider the renaming of these Magnificent and Fabled Military Installations." We need a President who believes #BlackLivesMatter and wants to heal America. #EndRacismNow. #Biden2020