LEXINGTON, Mo. — Joshua Hawley was 13 years old, living comfortably as the son of a bank president, when his parents gave him a book about political conservatism for Christmas.

Hawley became enamored with the ideology. He began writing columns for the local newspaper that seethed with resentment against the political power structure. Even domestic terrorist Timothy McVeigh's bombing of a federal building, killing 168 people, sparked him to speak up for groups that express anger toward the government.

"Many of the people who populate these movements are not radical right-wing pro-assault weapons freaks as they were stereotyped in the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing," he wrote.

Twenty-six years later, those far-right rumblings reached a crescendo during another deadly attack on a federal building — this time with Hawley at the center of the action.

As a U.S. senator, Hawley had led the charge to object to the 2020 election on the false premise that some states failed to follow the law, bolstering the baseless claims from President Donald Trump that the election was stolen and should be overturned. Hawley had said the ascent of Joe Biden to the presidency "depends" on what would happen on Jan. 6, the day of a pro forma congressional vote to affirm the election. He had been photographed that day pumping his fist in the air as some Trump supporters were gathering on the grounds outside the U.S. Capitol.

Later, as rioters ransacked the building and several senators huddled in a secure room, fearing for their lives and trying to persuade their pro-Trump colleagues to withdraw their efforts to undermine democracy, Hawley remained combative in pushing the very falsehoods that had helped stoke the violence.

At 41, the freshman senator had become a face of a movement built on the lie that the 2020 election was fraudulent.

"You have caused this!" Sen. Mitt Romney (R-Utah) erupted at him, referring to the events building up to the storming of the Capitol, according to a person familiar with the exchange, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private conversations.

Over the course of his rapid rise in politics — from law school professor to state attorney general to his 2018 election to the Senate — Hawley has followed two parallel paths, each reflecting a different political persona.

On one, he has pursued elite privilege, even relative to other senators, commuting to a private high school, attending Stanford University and Yale Law School, clerking at the Supreme Court, and working for a powerful Washington law firm, all while courting liberal professors and establishment Republicans who enabled his ascent.

On the other, he has expressed sympathy with some of the country's most far-right, anti-government extremists, demonstrating a willingness to see the world through their grievance-infused prism even after horrific attacks — from Oklahoma City in 1995, when he was 15, to the Capitol attack in 2021.

In the wake of Jan. 6, Hawley has made clear that he is committed to just one of those personas. It is the one that propelled him to promote Trump's baseless election claims and help inspire an insurrection — and it has made Hawley an instant star in today's far-right Republican Party.

Now, former friends and supporters — a middle school classmate, a law school professor, a conservative columnist who promoted him and the Republican stalwart who recruited him to run for the Senate — say they are shocked that he has become a different politician than they expected, describing themselves as victims of political deception and personal betrayal.

"I feel very responsible for Josh Hawley being in the Senate. I feel terrible about it," said former senator John C. Danforth (R-Mo.), who recently called his encouragement of Hawley's Senate run the "greatest mistake of my life." He added, "Josh Hawley played a central role in creating if not the darkest day in American history, one of the darkest days in American history."

Hawley declined to comment for this article. In an interview last week with Washington Post Live, which he scheduled to promote his just-published book, he stood by his decision to challenge the electoral college results. "In terms of having a debate about election integrity, I promised my constituents I would. I did. And I don't regret that at all," he said. Hawley condemned the actions of Jan. 6 as those of a "lawless criminal mob" and said that he considers President Biden to have been legitimately elected.

To combat criticism that he is an elitist, Hawley has urged people to examine the place where he grew up. "I come from a town called Lexington, Missouri," he said in his maiden Senate speech. "It's a place that reflects the dignity and quiet greatness of the working man and woman. These are the people who explored a continent, who built the railroads, who opened the West."

That, however, is a simplistic description.

A racist legacy

Lexington, a city of 4,700 by the Missouri River in a region still known as Little Dixie for its historical ties to the Confederacy, prides itself as a place rich in history.

But the history long told in Lexington, including during Hawley's childhood, focused almost entirely on the story of Whites who backed the Confederacy, including a battle in which Union forces were defeated. Nowhere in town is there a commemoration of the fact that it was also here that thousands of Blacks were enslaved in the 19th century, the largest such concentration in Missouri, according to Gary Gene Fuenfhausen, president of Missouri's Little Dixie Heritage Foundation.

"That's not something we talked about," said Mayor Joe Aull, who was superintendent of schools when Hawley was a student. "I just never really heard it mentioned."

Lexington's lack of recognition of its role in slavery has meant that the city did not have the kind of introspection about inequality that might have broadened Hawley's outlook, according to his former classmates.

"It's a small town. There's a lot of ignorance and a lot of people that don't leave the county and see the world," said Patrick Keller, who went to school with Hawley. "He had an insular life in this small town."

[Read two of the Lexington News columns Josh Hawley wrote as a teenager in the 1990s]

Hawley has said he was politically influenced by a Christmas gift from his parents when he was 13 years old, a book by a conservative columnist.

"I read George Will religiously," Hawley later wrote about the columnist, whose work has long appeared in The Washington Post. He also was influenced by listening to Rush Limbaugh, the fiery conservative radio star, according to a classmate.

Andrea Randle, who went to school with Hawley from second to eighth grades and served with him in student government, initially was impressed. She recalled that, when she was one of a handful of Blacks at Lexington Middle School, he worked with her on an initiative for a middle school graduation ceremony that was designed to include people from all backgrounds.

"I thought he was being inclusive," she said. Only later, like a number of other key figures in Hawley's life, would she decide that she had been misled.

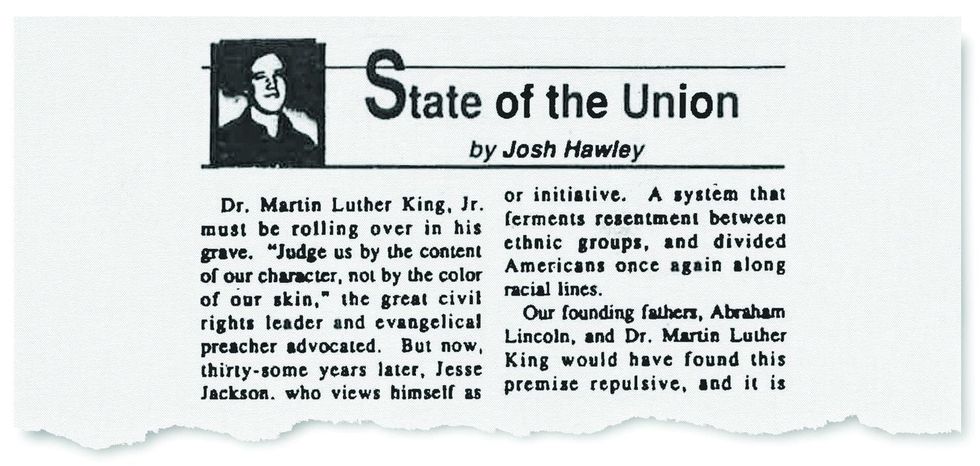

By the time Hawley completed middle school, his parents decided that he needed a more elite education and transferred him to Rockhurst High School in Kansas City, a Jesuit institution. As Hawley commuted to the school, he began his sideline as a conservative columnist for the Lexington News. His first column was titled "A Younger Point of View." The following columns, which ran in 1994 and 1995, were called more grandly "State of the Union." He said little in any columns about youth; he opined almost entirely about national political matters. The newspaper's former editor said in an interview that he didn't change a word, sending the columns directly to the typesetter.

In his column on the Oklahoma City bombing, which has received new attention after the Kansas City Star recently reported on it, Hawley wrote approvingly about an analyst who said that "the majority of these people who feel the U.S. government is involved in a 'conspiracy' against its citizens are average, middle-class Americans. … Dismissed by the media and treated with disdain by their elected leaders, these citizens come together and form groups that often draw more media fire as anti-government hate gatherings."

As a result, Hawley concluded, they become "disenchanted" and believe " 'conspiracy theories' about how the federal government is out to get them. … Those militias and 'hate' groups about which you read with your morning coffee are symptoms that mustn't go unnoticed."

In another column, which continues to upset Blacks who grew up with Hawley, he wrote that affirmative action programs designed to combat centuries of racism were a "perverted racial spoils system," claiming that the slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. would find it "repulsive," even though King had said that such programs were essential before equality could be achieved.

A mentor is disturbed

As a history major at Stanford, Hawley met professor David Kennedy, who suggested a number of books on the American presidency for Hawley to read. Kennedy said in an interview that he was astonished when his student returned a couple of weeks later and made clear that he had read and absorbed the volumes.

Kennedy became Hawley's academic adviser and oversaw his thesis, which became a book, "Theodore Roosevelt: Preacher of Righteousness." Kennedy wrote in the preface that Hawley had "an unusually questing intelligence, a breadth and depth of learning well beyond his years, and an intolerance for conventional thinking."

In an interview, Kennedy said Hawley was one of the best students he had ever taught, but, like many others who helped enable Hawley's rise, he now has deep regrets, saying he is "quite disturbed" about the senator's role on Jan. 6.

"I think he is a thoughtful, deeply analytical person," Kennedy said. "What I understand far less well is his particular political evolution. I had no inkling really just how conservative he was. I blame myself. The feeling on my part is that I simply was not paying attention to what he was doing in the arena of student culture where he was moving."

Hawley became president of a conservative group called the Freedom Forum and wrote for a conservative magazine, the Stanford Review. In a letter published by the magazine that foreshadowed his strategy of using race and sexual orientation as political weapons, Hawley in 1999 mocked Democrats whose "self-righteous pronouncements on racial oppression and gay rights activism seem oddly out of place, like disco music at a swing dance."

After Stanford, Hawley spent nearly a year in London teaching at the exclusive St. Paul's School, an institution that says it is for "gifted boys." Then Hawley, who had written in one of his Lexington News columns that people educated in the Ivy League were "elitist," attended Yale Law School. He became president of the Yale chapter of the conservative Federalist Society.

He then won a succession of coveted clerkships, first for Michael McConnell, a U.S. Court of Appeals judge, and then for Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. during the Supreme Court's 2006-07 term. That led to work at a Washington law firm then known as Hogan & Hartson and next at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, where Hawley was co-counsel on the Hobby Lobby case, in which the Supreme Court ruled 5 to 4 in 2014 that certain corporations could not be required to pay for insurance covering contraception, a major victory for conservatives.

Hawley returned to Missouri with an eye toward laying the ground for a political career. His availability caught the attention of Thom Lambert, a University of Missouri law professor. Lambert aggressively recruited Hawley and his wife, Erin, to teach in Columbia.

Lambert, who said he is a gay evangelical Christian, said that after Hawley spent several semesters teaching at the university, he became alarmed that Hawley began making pronouncements that didn't square with his background in constitutional law but instead appeared designed to attract political support. Lambert was especially shocked in 2015 when Hawley, then a candidate for attorney general, weighed in on a Kentucky case in which a county clerk was arrested for refusing to give a same-sex couple a marriage license or to allow her deputies to do so, citing her religious beliefs. Hawley said it was "tragic" that the clerk was arrested, and he promised to protect such government officials if he were elected.

"This is the moment when I realized, I'm not sure I know this guy," Lambert said. "He was trying to establish his credentials as a religious-freedom warrior. This is where I thought, you're kind of lying here. You're misrepresenting how the Constitution works."

A broken promise

Hawley won the race with the help of a television ad in which he blasted politicians who he said are "just climbing the ladder, using one office to get another." The ad showed several men climbing ladders.

But within months of winning the office, Hawley prepared to do exactly what he had mocked: climb the ladder to become a senator. He needed a way to explain to voters why he was breaking his promise. A fortuitous encounter provided a path.

Danforth, the former senator from Missouri, had delivered a speech years earlier at Yale, and Hawley sat next to him later at a small dinner. Now Danforth, who also had served as Missouri's attorney general, was looking for a candidate to run against Democratic Sen. Claire McCaskill.

A moderate establishment figure, Danforth by this time had emerged as one of Trump's harshest critics, and he believed that Hawley could bring a principled vision to the Republican Party.

"You have the training and the ability to be a leading voice for the constitutional order, not only in Missouri but nationally," Danforth wrote to Hawley in a letter co-signed by three other former Missouri Republican senators.

With Danforth's letter helping provide an excuse, Hawley broke his vow against "climbing the ladder" and announced his Senate candidacy in October 2017.

Hawley, an evangelical, had seen how Trump captured the presidency in 2016, in part by winning the White evangelical vote by 80 to 16 percent.

So, when Hawley spoke before a group of ministers in Kansas City in December 2017, he sounded like a different person than the one who had written five years earlier that there were "distinct missions of church and state — is it really the role of government, for instance, to promote 'Christian values' or refurbish America's Christian heritage?" The state, he had written, should not be used "to convert non-believers."

But in his 2017 speech, he advocated going into "the public realm and to seek the obedience of the nations, of our nation … to transform our society to reflect the gospel truth and lordship of Jesus Christ."

The speech drew a rebuke from the Freedom From Religion Foundation, which is dedicated to upholding the separation of church and state. The foundation wrote to the former constitutional law professor that his remark "stands in glaring defiance of the very Constitution that you swore an oath to uphold."

Tying himself as closely as possible to Trump, Hawley beat McCaskill, 51 percent to 46 percent, and headed to Washington.

'What's with Hawley?'

Then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) had played a crucial role, helping to fundraise for Hawley's campaign. But the incoming senator would not say that he supported McConnell having another term leading the party. McConnell asked Danforth for an explanation.

"What's with Hawley?" he asked, according to Danforth. (A McConnell spokesman, asked about the call, responded that "McConnell never solicited Hawley's support for his leadership election and he ran unopposed.")

Danforth said he called Hawley, who told him, "I'm going to go to Washington, and I'm not going to be part of the establishment, and I'm not going to be pushed around. I'm going to be independent, and I'm going to speak for the people."

Danforth told The Post that Hawley's "response was so aggressive that it struck me as strange." Nonetheless, he remained supportive, dining with the senator-elect and writing a warm congratulatory note. But Hawley shut him off. He didn't respond to Danforth's letter, and the two have not spoken since their post-election meal, Danforth said.

"I think he would not be in the U.S. Senate except for me," Danforth said. "Maybe that sounds like I'm promoting myself being a kingmaker, but my view is, I put him there and created this thing."

Hawley awaits a speech by President Donald Trump at a 2018 campaign rally in Springfield, Mo. (Evan Vucci/AP)

Hawley made a striking declaration about his view of Americans in a June 2019 article in Christianity Today, titled "The Age of Pelagius." He said Pelagius, a Greek scholar born about the year 350, had said individuals had freedom to be whatever they chose. "It's the Pelagian vision," he wrote. "Liberty is the right to choose your own meaning."

Hawley found such liberty abhorrent.

He said it meant that an individual could "emancipate yourself not just from God but from society, family, and tradition." He said those seeking this liberty became elitists.

This was too much for his onetime hero, George Will, who viewed individual liberty as an essential American trait. Will had been helpful during the Senate campaign. He had been urged to write about Hawley by Danforth, his longtime friend and the godfather of Will's daughter. Will came to Missouri, rode with Hawley on a campaign bus and wrote a column praising the candidate as "an actual, not a pretend, conservative."

But Will gradually concluded that his assessment had been wrong. He wrote a column in January 2020 ridiculing Hawley's attack on individualism. As the two feuded, the senator fired off a Trump-like tweet at the man he once revered: "I'm told NeverTrumper and ex-Republican George Will attacking me again today for talking about working people. Oh George. Don't you have a country club to go to?"

Will said in an interview that he found the tweet "surpassingly dumb." He later condemned Hawley's effort to reject the presidential election results and create a "synthetic drama" on Jan. 6, writing that the senator from Missouri, along with Trump and Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Tex.), must be "forevermore shunned. … Each will wear a scarlet 'S' as a seditionist."

The feud with Will — like the one with Danforth and other former key backers — demonstrated how separated Hawley had become from the establishment Republicans who had helped him win the Senate seat.

He moved further to the right, distancing himself from yet another mentor, Chief Justice Roberts. He pilloried last year's 6-to-3 ruling by the Supreme Court extending civil rights protections to gay and transgender people. It was a decision written by Trump nominee Neil M. Gorsuch and supported by Roberts, for whom Hawley had clerked. But Hawley declared that "it represents the end of the conservative legal movement."

Hawley then zeroed in on an issue that Trump had turned into a racial flash point: efforts to educate leaders about the history of racism to promote diversity in the workplace.

Under "critical race theory," companies and government entities have examined the institutionalized racism that has marginalized minorities to low-level positions. Trump had issued an executive order, supported by Hawley, that prevented federal contracts from having such diversity training.

The senator, in a Nov. 30 tweet, echoed his column against affirmative action, written 25 years earlier. "Corporate liberals … love critical race theory and all the other warmed-over Marxist garbage," he wrote. "They sell out working Americans and sneer at them at the same time. That's the New Left."

Kimberlé Crenshaw, a UCLA law professor who coined the phrase "critical race theory," said in an interview that Hawley is attacking her concept as a means of "race baiting."

"He walks in the footsteps of many demagogues in America's historical past, whose trajectory into the center of power has been through racialized scapegoating," Crenshaw said.

A classmate reaches out

Andrea Randle, who had worked with Hawley on the middle school graduation ceremony, thought of her childhood friend after hearing about the killing of George Floyd, who died last year after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for more than nine minutes.

Randle said in an interview that she hoped Hawley could once again work with her, believing he could join the fight for racial justice. She sent him an email with the subject line: "Old Ally from Lexington."

"Hi Josh," she wrote on May 31, 2020. "I know you remember me. We grew up together in rural Lexington, ran student council & sang in honor choir. … You were always going to move on to do great things. … The death of George Floyd will be forever etched in every memory & in history. I haven't seen where you have spoken out about it."

Urging Hawley to be a leader on the issue, she wrote: "I know the young man who looked into the future & created an 8th grade commemoration … for our small little class of 98 lead[s] with empathy. America needs him desperately right now."

Randle said Hawley never responded, which deeply disappointed her. "I was hoping he would be on the right side of history of this," she said.

A month later, Hawley went on Fox News and attacked the Black Lives Matter movement as "Marxist" and belittled its efforts to fight for justice in the aftermath of Floyd's death. He said it has "hatred for the United States of America" and that "the organization is trying to hijack any movement towards justice for George Floyd, for instance, they're trying to hijack that conversation away towards their own political Marxist agenda."

To Randle, Hawley's dismissal of a group dedicated to civil rights for Blacks and his call to abolish affirmative action are rooted in what she said is his lack of empathy concerning the legacy of slavery in Lexington. She concluded that her initial impression of him as an inclusive person was wrong.

"It just doesn't seem like that person he was is the person he is today," Randle said. "It's disappointing and disheartening. This denial of facts, the denial of the people who are marginalized in our culture, that there are historical systems in place that are still keeping people down. That he won't even acknowledge it is just kind of crazy to me.

'Thanks Josh!'

After the electoral college vote giving Biden the presidency, McConnell wanted to head off the possibility that a single senator could force a vote in Congress on certifying the results. His prime concern was that Hawley would "breach the dam," as an associate put it, and prompt other senators to follow him. He declared that "the electoral college has spoken" and urged senators to accept the result.

Hawley went ahead anyway.

He announced on Dec. 30 that he would challenge the results, prompting some other senators to follow his lead. Hawley defied McConnell despite the fact that more than 90 federal and state judges had rejected lawsuits seeking to overturn the outcome and Trump's attorney general, William P. Barr, had dismissed allegations that there was widespread voter fraud.

Hawley focused on Pennsylvania, saying the state had violated its constitution by widening access to mail-in ballots. But it was a Republican-controlled legislature that approved universal mail voting in 2019, and the GOP had encouraged its use. When Trump lost the state, his allies sought to get those votes thrown out, but the effort was rejected by the courts.

The next day, McConnell tried again to head off Hawley, overseeing a conference call that was supposed to include all Republican senators. McConnell said the Jan. 6 vote was the most consequential of his life, and he asked why Hawley was going forward with an effort doomed to fail. The plan was for Hawley to explain himself and for Sen. Patrick J. Toomey (R-Pa.) to rebut his assertions, according to a person familiar with the meeting, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe private discussions.

The senators waited for Hawley to respond but heard no reply. They did not realize, as Politico first reported, that Hawley had not dialed in as expected. Hawley then sent a fundraising letter that said he wouldn't give in to "the Washington and Wall Street establishment."

Two days after the teleconference, Toomey tweeted that Hawley and others "fail to acknowledge that these allegations have been adjudicated in courtrooms across America and were found to be unsupported by evidence."

Trump, however, encouraged Hawley, tweeting, "Thanks Josh!" The senator then went on Fox News, where anchor Bret Baier asked about his plans to challenge the electoral college results. "Are you trying to say as of January 20 Trump will be president?" Baier asked.

"That depends on what happens on Wednesday [Jan. 6]; that's why we have the debate," Hawley said.

"No it doesn't," Baier responded, saying that most experts believe Congress does not have the right to overturn the certification.

A few days later, on Jan. 6, the president praised Hawley during his incendiary speech to supporters. Around that time, Hawley passed by a crowd of protesters at the Capitol and raised his fist in solidarity. Shortly thereafter, as he and other senators were on or near the Senate floor, a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol.

Senators were rushed to the safety of a secure room in an adjoining Senate office building. At that tense moment, fearing that their lives were at risk if rioters found them, a number of senators gathered in the secure room to discuss whether they could shut down the effort to challenge the election results. One senator recalled that every time he looked over, he saw Hawley "standing by himself in a corner," according to a person familiar with the matter, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, confirming a detail first reported by the Wall Street Journal.

Romney, in a floor speech directed at Hawley and others, tried one last time to stop the challenges.

"Those who choose to continue to support [Trump's] dangerous gambit by objecting to the results of a legitimate, democratic election will forever be seen as being complicit in an unprecedented attack against our democracy," said the senator from Utah, who declined to comment.

Hawley insisted he would proceed with his challenge to the Pennsylvania results. The Senate defeated his effort by a vote of 92 to 7.

Hawley later said that "it is a lie that I was trying to overturn an election," and he has consistently condemned those who stormed the Capitol. But he has stood by his claim that Pennsylvania's vote was unconstitutional and wrote that he was reflecting constituent "concerns about election integrity." He did not point out that such concerns exist largely because Hawley, Trump and their allies stoked them with false claims.

'We love Josh Hawley'

Hawley's position has increasingly taken hold in the party, where leaders at every level have embraced the false claims of election fraud. Trump remains the most popular figure in the country among GOP voters, and lawmakers who opposed the electoral college challenge have been booed at home and faced withering criticism from local party officials.

Hawley raised $3 million in the first quarter of this year, according to federal records, and he has audaciously cast himself as the person best suited to redefine the GOP.

On April 17, in his first public appearance in Missouri since the events of Jan. 6, Hawley traveled to Ozark, a city in the state's southwestern corner where he is building a new home, and strode into his fan base at Ozark High School, home of the Tigers. He was swarmed by several hundred people who had gathered at a Lincoln Day dinner fundraiser for Christian County's Republican Party.

"We love Josh Hawley because he stands up for Missouri's values," said Wanda Marteen, 78, who organized the event. "The first thing, the big thing he stood up for, is the election. We feel like it was fraudulent."

Most of the speech amounted to an outline of his effort to remake the Republican Party and possibly seek the presidency. Hawley blasted what he called "the giant woke corporations" that opposed a Republican-backed Georgia voting measure, said Democrats would "effectively cancel women's sports" by allowing transgender athletes and argued that they back legislation "that would effectively close Christian colleges and universities."

Five days after his Ozark speech, Hawley became the lone senator to vote against the Covid-19 Hate Crimes Act, designed to combat discrimination against Asian Americans. It was in some respects an unlikely position for someone eyeing a presidential campaign, but to Hawley, it made sense. It was, he said, "dangerous" to broaden the federal government's ability to prosecute hate crimes.

Hawley had taken his stand. Once again, he was defiant, beckoning others to follow.

Michael Kranish, Washington Post, May 11, 2021

###

May 12, 2021

Voices4America Post Script. This is an amazing must-read.

Did you see the DeCaprio movie, The Amazing Mr Ripley? Like Ripley, Hawley is a psychopath who behaves in one way to one person and another to another. Sick, dangerous man.

Share the biography of a psycho-Seditionist! #JoshHawley