Most modern Presidents chart their opening moves with the help of a friendly think tank or a set of long-held beliefs.

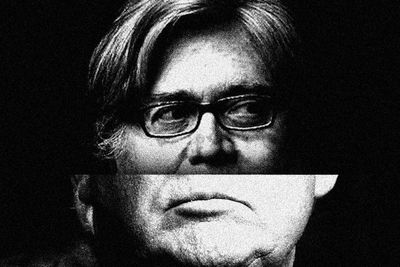

Donald Trump's first steps had the feel of a documentary film made by his chief strategist and alter ego Stephen K. Bannon, a director who deploys ravenous sharks, shrieking tornadoes and mushroom clouds as reliably as John Ford shot Monument Valley.

Act I of the Trump presidency has been filled with disruption, as promised by Trump and programmed by Bannon, with plenty of resistance in reply, from both inside and outside the government. Perhaps this should not be surprising. Trump told America many times in 2016 that his would be no ordinary Administration. Having launched his campaign as a can-do chief executive, he came to see himself as the leader of a movement–and no movement is complete without its commissar. Bannon is the one who keeps the doctrine pure, the true believer, who is in it not for money or position, but to change history. "What we are witnessing now is the birth of a new political order," Bannon wrote in an email to the Washington Post.

This forceful presence has already opened cracks in West Wing. The Administration was barely a week old when, on the evening of Jan. 27–with little or no explanation to agency heads, congressional leaders or the press–Trump shut down America's refugee program for 120 days (indefinitely in the case of Syrian refugees), while barring travelers from seven majority-Muslim countries. Almost immediately, U.S. customs and border agents began collaring airline passengers covered by the order, including more than 100 people whose green cards or valid visas would have been sufficient for entry if only they had taken an earlier flight. Protesters grabbed markers and cardboard scraps and raced to airports from coast to coast, where television cameras found them by the thousands.

As the storm reached the gates of the White House on Saturday, many of the West Wing's senior staff had departed to attend the secretive Alfalfa Club annual dinner, an off-the-record black-tie soiree where politicos drink and tell jokes with billionaires. But Bannon avoided this gathering of the elites he believes to be doomed, and remained at the White House to continue the shock and awe.

Having already helped draft the dark and scathing Inaugural Address and impose the refugee ban, Bannon proceeded to light the national-security apparatus on fire by negotiating a standing invitation for himself to the National Security Council. His fingerprints were suddenly everywhere: when Trump tweeted on Jan. 30 that the national media was his "opposition party," he was echoing Bannon's comment a few days earlier to the New York Times.

There is only one President at a time, and Donald Trump is not one to cede authority. But in the early days at 1600 Pennsylvania, the portly and rumpled Bannon (the only male aide who dared to visit Trump's office without a suit and tie) has the tools to become as influential as any staffer in memory. Colleagues have dubbed him "the Encyclopedia" for the range of information he carries in his head; but more than any of that, Bannon has a mind-meld with Trump. "They are both really great storytellers," says Kellyanne Conway, counselor to the President, of their bond. "The President and Steve share an important trait of absorbing information and weighing consequences."

They share the experience of being talkative and brash, pugnacious money magnets who never quite fit among the elite. A Democrat by heritage and Republican by choice, Bannon has come to see both parties as deeply corrupt, a belief that has shaped his recent career as a polemical filmmaker and Internet bomb thrower. A party guest recalled meeting him as a private citizen and Bannon telling him that he was like Lenin, eager to "bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today's Establishment."

And by different paths, he and Trump have found themselves at the same philosophical destinations on issues of trade, immigration, public safety, the environment, political decay and much more.

Yet Bannon's prominence in the first 10 days of the Administration–and the scenes of confusion and disorder that are his disruptive hallmark–has rattled the West Wing and perhaps even dismayed the President. According to senior Administration officials, Trump hauled in some half-dozen of his key advisers for a brisk dressing-down. Everything goes through chief of staff Reince Priebus, he directed. Nothing flows that hasn't been scheduled by his deputy Katie Walsh. "You're going to see probably a slower, more deliberative process," one official told TIME.

Still, Bannon possesses that dearest of Washington currencies: walk-in privileges for the Oval Office. And he is the one who has been most successful in focusing Trump on a winning message. While other advisers have tried to change Trump, Bannon has urged him to step on the gas.

Both of these images, the orderly office and the glorious crusade, have genuine appeal for the President. And they will likely continue to pull him in opposite directions. By marking Trump's first days so vividly, Bannon has put the accent on Trump the disrupter. In that sense, as one veteran Republican said, "It's already over, and Bannon won."

People who have studied one of Donald Trump's favorite books, The Art of the Deal, are aware that he sees grandstanding, trash-talking, boasting and conflict as useful ingredients in the quest for success. "My style of dealmaking is quite simple and straightforward," he declares in his opus. "I aim very high, and then I just keep pushing and pushing and pushing to get what I'm after."

Perhaps no place in the U.S. is more adamantly resistant to pushing than Washington. But Trump won the election in part by understanding that this is no ordinary time. Technology has placed a communications revolution in nearly every American palm. When mixed with the economic frustrations of a globalized economy, this power unleashed a new populism. In the history of human beings, it has never been easier to organize groups, for good or ill, or to communicate both truth and lies, to question authority and to undermine the answers that authority gives. Trump leveraged this growing power to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of power–the media, the political parties, the elected and unelected bosses.

Bannon's background at Breitbart taught him the same lessons. Founded as an alternative to mainstream media by the late Andrew Breitbart, the website was an immediate disruptive force in U.S. politics. Ask Anthony Weiner. In 2011, the New York Congressman was a darling of the Democratic grassroots with sky-high ambitions. Then Breitbart published a screen grab from Weiner's Twitter feed that opened a door on his late-night sexting habits. Social media did the rest. The sudden death of the founder in 2012 placed his friend Bannon in command. As the site ramped up its video, radio and merchandising and opened several bureaus overseas, Breitbart honed the art of the inflammatory headline and offered a home to the bullyboys of the so-called alt right, including those determined to elevate the abhorrent ideals of white nationalism.

The essence of the place could be found in a viral video that made its debut around the time of Bannon's takeover of Breitbart. Over a piece of old nature footage, a clever narrator commented on a single-minded beast known as a honey badger. Through bee stings, snakebites and other degradations, the animal never stops killing and eating. "Honey Badger don't give a shit," the narrator summed up. Bannon adopted the phrase as a motto.

Official Washington and its counterparts around the globe are struggling to understand just how much the honey badgers are now running the show. There is no doubt the badgers are starving for change and don't care if they get stung by swarms of pundits, incumbents, lobbyists and donors–not to mention foreign leaders and denizens of Davos. In fact, they seem to like it.

The capital was in a lather over the immigration order, with denunciations pouring in from Republicans and Democrats alike. Rumors swirled of resignations from the Trump White House, when Trump's policy badger, Stephen Miller, a Bannon ally, calmly stepped before the cameras. "Anytime you do anything hugely successful that challenges a failed orthodoxy, you're going to see protests," he told CBS News. "In fact, if nobody is disagreeing with what you're doing, then you're probably not doing anything that really matters in the scheme of things."

The withering fire Trump has drawn from nearly every direction would normally have a President backpedaling. Not the badgers. In Trump country, the vast red sea of Middle America where the President won the election, many people welcomed the squeals of the outraged elites. As one delighted Kansas City businessman put it, "He's upsetting all the right people."

Bannon helps Trump remember that he never made a priority of being a uniter, as George W. Bush did, nor did he offer to heal our divisions in the manner of Barack Obama. The new President has crafted himself as a defender of the "forgotten people," which places in his sight those with powerful names you already know. With new goals came new thinking. "People tell us that things have always been done a certain way," said one trusted Trump aide. "We say, Yes, but look at the results. It hasn't worked. We're trying a new way."

On this Trump and Bannon agree. What happens next is the mystery. Trump, in his long past as a businessman, has always aimed his disruptions at the goal of an eventual handshake: the deal. Bannon, in his films and radio shows, has shown a more apocalyptic bent.

Sometime in the early 2000s, Bannon was captivated by a book called The Fourth Turning by generational theorists William Strauss and Neil Howe. The book argues that American history can be described in a four-phase cycle, repeated again and again, in which successive generations have fallen into crisis, embraced institutions, rebelled against those institutions and forgotten the lessons of the past–which invites the next crisis. These cycles of roughly 80 years each took us from the revolution to the Civil War, and then to World War II, which Bannon might point out was taking shape 80 years ago. During the fourth turning of the phase, institutions are destroyed and rebuilt.

In an interview with TIME, author Howe recalled that Bannon contacted him more than a decade ago about making a film based on the book. That eventually led to Generation Zero, released in 2010, in which Bannon cast the 2008 financial crisis as a sign that the turning was upon us. Howe agrees with the analysis, in part. In each cycle, the postcrisis generation, in this case the baby boomers, eventually rises to "become the senior leaders who have no memory of the last crisis, and they are always the ones who push us into the next one," Howe said.

But Bannon, who once called himself the "patron saint of commoners," seemed to relish the opportunity to clean out the old order and build a new one in its place, casting the political events of the nation as moments of extreme historical urgency, pivot points for the world. Historian David Kaiser played a featured role in Generation Zero, and he recalls his filmed interview with Bannon as an engrossing and enjoyable experience.

And yet, he told TIME, he was taken aback when Bannon began to argue that the current phase of history foreshadowed a massive new war. "I remember him saying, 'Well, look, you have the American revolution, and then you have the Civil War, which was bigger than the revolution. And you have the Second World War, which was bigger than the Civil War,'" Kaiser said. "He even wanted me to say that on camera, and I was not willing."

Howe, too, was struck by what he calls Bannon's "rather severe outlook on what our nation is going through." Bannon noted repeatedly on his radio show that "we're at war" with radical jihadis in places around the world. This is "a global existential war" that likely will become "a major shooting war in the Middle East again." War with China may also be looming, he has said. This conviction is central to the Breitbart mission, he explained in November 2015: "Our big belief, one of our central organizing principles at the site, is that we're at war."

The little firm won major clients, including Samsung, MGM and Italy's answer to Trump, the billionaire and future Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Bannon's biggest score, though, was not immediately apparent. In 1993, cable-television mogul Ted Turner bought Castle Rock Entertainment in a deal that Bannon helped deliver, and as Bannon has told the tale, at the last moment Turner insisted that the banker put some skin in the game. Instead of cash only, Bannon & Co. received a piece of five Castle Rock television shows–including a struggling sitcom called Seinfeld.

Meanwhile, Bannon was gradually evolving from dealmaker to filmmaker, with an unusual detour to manage a troubled experiment in the Arizona desert called Biosphere 2. In 1999, he served as co–executive producer of Titus, a star-studded adaptation of a Shakespeare play that went nowhere. Turning to documentaries that he wrote and directed himself, Bannon became a sort of Michael Moore of the right, with films celebrating Ronald Reagan, Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann.

Bachmann, a former member of Congress from Minnesota, says Bannon was able to see what the mainstream media either could not or would not. There was a rising tide of disgust in America, which the coastal elites dismissed in "a grotesque caricature of what Donald Trump has called the forgotten man," Bachmann says. "He was simply trying to give voice, I think, and give a platform to people who were not only being ignored but who were being lied about in the mainstream media."

Bannon's life became a crusade against political, financial and cultural elites of all stripes. Bannon's philosophical transformation showed in his clothes: no one could look at his preferred uniform of T-shirts, cargo shorts and stubble and think Goldman Sachs.

At Breitbart, Bannon was a volcanic figure, according to a number of former staff members who found themselves crossways with the boss. Republican consultant John Pudner, a Bannon friend who briefly worked at Breitbart as the editor of a sports section, recalls the time Bannon "reamed me out"–just hours before he turned around and connected his friend with a plum new job. "He could hit you with that level of intensity and at the same time be singing your praises," he said.

Not everyone is charitable. "He is legitimately one of the worst people I've ever dealt with," former Breitbart editor Ben Shapiro told TIME last year. "He regularly abuses people. He sees everything as a war. Every time he feels crossed, he makes it his business to destroy his opponent." The sentiment was echoed by conservative commentator Dana Loesch, a former Breitbart employee. "One of the worst people on God's green earth," she said on her radio show last year. Bannon was charged with domestic violence after a dispute with his ex-wife in 1996, though she declined to testify against him and the case was dropped. She later claimed in legal papers that Bannon had objected to a private school for their daughters because there were a lot of Jewish students attending and he didn't like the way they are raised to be "whiny brats." Bannon denied those claims, and declined through a White House spokesperson a request from TIME to comment for this story.

In Trump, Bannon found his ultimate outsider. He frequently had the candidate on his radio show, and former staffers say he ordered a steady stream of pro-Trump stories. Now Bannon's imprint can be seen on presidential decisions ranging from the hiring of former Breitbart staffers to key White House positions to the choice of Andrew Jackson's portrait–a Bannon idol–for display near the President's desk.

"Where Bannon is really having his instinct is on the policy front," says a longtime Trump ally. Which policies? "All of them. He's Trump's facilitator." In a Trump White House, this adviser says, you can only get–and keep–as much power as the President wants you to have. But Trump and Bannon "sat down before the election and made a list of things they wanted to do in office right away," says this adviser. Trump is the one deciding which items to tick off. "Bannon's just smart enough to give him the list."

However much the disruptive Trump may have welcomed the outrage of the ruling elites, the slash-and-burn style has caused real internal tension at the White House. Senior staff say Trump has instructed chief of staff Priebus to enforce more orderly lines of authority and communication from now on. Presidential counselor Conway has agreed to take an increased role in planning White House messaging with the policy and legal shops.

The internal tribulations of the past few weeks are a clear cause for worry. The decision to rush the refugee order through a relatively secret process came after Bannon and Miller noticed that documents circulated through the National Security Council's professional staff were leaking to the press, according to Administration sources. Bannon and Miller moved to curtail access to forthcoming memos and drafts. Members of Congress, and even some Cabinet members, were cut out of the loop or had their access sharply limited.

As a result, the sources said, after the controversial order was signed, confusion reigned. An unknown number of holders of green cards and valid visas were en route to the U.S. The initial White House guidance was that they should all be turned back. But as immigration and civil-liberties lawyers rushed to federal court to challenge the order, the White House reversed itself, saying green-card holders would be granted waivers. Reporters had difficulty finding out even basic facts, like the names of the countries from which travel was banned. Days later, the President even intervened to amend the order that appointed Bannon to a regular spot on the National Security Council. Trump wanted his CIA director, Mike Pompeo, there too.

Most modern Presidents chart their opening moves with the help of a friendly think tank or a set of long-held beliefs.

Donald Trump's first steps had the feel of a documentary film made by his chief strategist and alter ego Stephen K. Bannon, a director who deploys ravenous sharks, shrieking tornadoes and mushroom clouds as reliably as John Ford shot Monument Valley.

Act I of the Trump presidency has been filled with disruption, as promised by Trump and programmed by Bannon, with plenty of resistance in reply, from both inside and outside the government. Perhaps this should not be surprising. Trump told America many times in 2016 that his would be no ordinary Administration. Having launched his campaign as a can-do chief executive, he came to see himself as the leader of a movement–and no movement is complete without its commissar. Bannon is the one who keeps the doctrine pure, the true believer, who is in it not for money or position, but to change history. "What we are witnessing now is the birth of a new political order," Bannon wrote in an email to the Washington Post.

This forceful presence has already opened cracks in West Wing. The Administration was barely a week old when, on the evening of Jan. 27–with little or no explanation to agency heads, congressional leaders or the press–Trump shut down America's refugee program for 120 days (indefinitely in the case of Syrian refugees), while barring travelers from seven majority-Muslim countries. Almost immediately, U.S. customs and border agents began collaring airline passengers covered by the order, including more than 100 people whose green cards or valid visas would have been sufficient for entry if only they had taken an earlier flight. Protesters grabbed markers and cardboard scraps and raced to airports from coast to coast, where television cameras found them by the thousands.

As the storm reached the gates of the White House on Saturday, many of the West Wing's senior staff had departed to attend the secretive Alfalfa Club annual dinner, an off-the-record black-tie soiree where politicos drink and tell jokes with billionaires. But Bannon avoided this gathering of the elites he believes to be doomed, and remained at the White House to continue the shock and awe.

Having already helped draft the dark and scathing Inaugural Address and impose the refugee ban, Bannon proceeded to light the national-security apparatus on fire by negotiating a standing invitation for himself to the National Security Council. His fingerprints were suddenly everywhere: when Trump tweeted on Jan. 30 that the national media was his "opposition party," he was echoing Bannon's comment a few days earlier to the New York Times.

There is only one President at a time, and Donald Trump is not one to cede authority. But in the early days at 1600 Pennsylvania, the portly and rumpled Bannon (the only male aide who dared to visit Trump's office without a suit and tie) has the tools to become as influential as any staffer in memory. Colleagues have dubbed him "the Encyclopedia" for the range of information he carries in his head; but more than any of that, Bannon has a mind-meld with Trump. "They are both really great storytellers," says Kellyanne Conway, counselor to the President, of their bond. "The President and Steve share an important trait of absorbing information and weighing consequences."

They share the experience of being talkative and brash, pugnacious money magnets who never quite fit among the elite. A Democrat by heritage and Republican by choice, Bannon has come to see both parties as deeply corrupt, a belief that has shaped his recent career as a polemical filmmaker and Internet bomb thrower. A party guest recalled meeting him as a private citizen and Bannon telling him that he was like Lenin, eager to "bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today's Establishment."

And by different paths, he and Trump have found themselves at the same philosophical destinations on issues of trade, immigration, public safety, the environment, political decay and much more.

Yet Bannon's prominence in the first 10 days of the Administration–and the scenes of confusion and disorder that are his disruptive hallmark–has rattled the West Wing and perhaps even dismayed the President. According to senior Administration officials, Trump hauled in some half-dozen of his key advisers for a brisk dressing-down. Everything goes through chief of staff Reince Priebus, he directed. Nothing flows that hasn't been scheduled by his deputy Katie Walsh. "You're going to see probably a slower, more deliberative process," one official told TIME.

Still, Bannon possesses that dearest of Washington currencies: walk-in privileges for the Oval Office. And he is the one who has been most successful in focusing Trump on a winning message. While other advisers have tried to change Trump, Bannon has urged him to step on the gas.

Both of these images, the orderly office and the glorious crusade, have genuine appeal for the President. And they will likely continue to pull him in opposite directions. By marking Trump's first days so vividly, Bannon has put the accent on Trump the disrupter. In that sense, as one veteran Republican said, "It's already over, and Bannon won."

People who have studied one of Donald Trump's favorite books, The Art of the Deal, are aware that he sees grandstanding, trash-talking, boasting and conflict as useful ingredients in the quest for success. "My style of dealmaking is quite simple and straightforward," he declares in his opus. "I aim very high, and then I just keep pushing and pushing and pushing to get what I'm after."

Perhaps no place in the U.S. is more adamantly resistant to pushing than Washington. But Trump won the election in part by understanding that this is no ordinary time. Technology has placed a communications revolution in nearly every American palm. When mixed with the economic frustrations of a globalized economy, this power unleashed a new populism. In the history of human beings, it has never been easier to organize groups, for good or ill, or to communicate both truth and lies, to question authority and to undermine the answers that authority gives. Trump leveraged this growing power to bypass the traditional gatekeepers of power–the media, the political parties, the elected and unelected bosses.

Bannon's background at Breitbart taught him the same lessons. Founded as an alternative to mainstream media by the late Andrew Breitbart, the website was an immediate disruptive force in U.S. politics. Ask Anthony Weiner. In 2011, the New York Congressman was a darling of the Democratic grassroots with sky-high ambitions. Then Breitbart published a screen grab from Weiner's Twitter feed that opened a door on his late-night sexting habits. Social media did the rest. The sudden death of the founder in 2012 placed his friend Bannon in command. As the site ramped up its video, radio and merchandising and opened several bureaus overseas, Breitbart honed the art of the inflammatory headline and offered a home to the bullyboys of the so-called alt right, including those determined to elevate the abhorrent ideals of white nationalism.

The essence of the place could be found in a viral video that made its debut around the time of Bannon's takeover of Breitbart. Over a piece of old nature footage, a clever narrator commented on a single-minded beast known as a honey badger. Through bee stings, snakebites and other degradations, the animal never stops killing and eating. "Honey Badger don't give a shit," the narrator summed up. Bannon adopted the phrase as a motto.

Official Washington and its counterparts around the globe are struggling to understand just how much the honey badgers are now running the show. There is no doubt the badgers are starving for change and don't care if they get stung by swarms of pundits, incumbents, lobbyists and donors–not to mention foreign leaders and denizens of Davos. In fact, they seem to like it.

The capital was in a lather over the immigration order, with denunciations pouring in from Republicans and Democrats alike. Rumors swirled of resignations from the Trump White House, when Trump's policy badger, Stephen Miller, a Bannon ally, calmly stepped before the cameras. "Anytime you do anything hugely successful that challenges a failed orthodoxy, you're going to see protests," he told CBS News. "In fact, if nobody is disagreeing with what you're doing, then you're probably not doing anything that really matters in the scheme of things."

The withering fire Trump has drawn from nearly every direction would normally have a President backpedaling. Not the badgers. In Trump country, the vast red sea of Middle America where the President won the election, many people welcomed the squeals of the outraged elites. As one delighted Kansas City businessman put it, "He's upsetting all the right people."

Bannon helps Trump remember that he never made a priority of being a uniter, as George W. Bush did, nor did he offer to heal our divisions in the manner of Barack Obama. The new President has crafted himself as a defender of the "forgotten people," which places in his sight those with powerful names you already know. With new goals came new thinking. "People tell us that things have always been done a certain way," said one trusted Trump aide. "We say, Yes, but look at the results. It hasn't worked. We're trying a new way."

On this Trump and Bannon agree. What happens next is the mystery. Trump, in his long past as a businessman, has always aimed his disruptions at the goal of an eventual handshake: the deal. Bannon, in his films and radio shows, has shown a more apocalyptic bent.

Sometime in the early 2000s, Bannon was captivated by a book called The Fourth Turning by generational theorists William Strauss and Neil Howe. The book argues that American history can be described in a four-phase cycle, repeated again and again, in which successive generations have fallen into crisis, embraced institutions, rebelled against those institutions and forgotten the lessons of the past–which invites the next crisis. These cycles of roughly 80 years each took us from the revolution to the Civil War, and then to World War II, which Bannon might point out was taking shape 80 years ago. During the fourth turning of the phase, institutions are destroyed and rebuilt.

In an interview with TIME, author Howe recalled that Bannon contacted him more than a decade ago about making a film based on the book. That eventually led to Generation Zero, released in 2010, in which Bannon cast the 2008 financial crisis as a sign that the turning was upon us. Howe agrees with the analysis, in part. In each cycle, the postcrisis generation, in this case the baby boomers, eventually rises to "become the senior leaders who have no memory of the last crisis, and they are always the ones who push us into the next one," Howe said.

But Bannon, who once called himself the "patron saint of commoners," seemed to relish the opportunity to clean out the old order and build a new one in its place, casting the political events of the nation as moments of extreme historical urgency, pivot points for the world. Historian David Kaiser played a featured role in Generation Zero, and he recalls his filmed interview with Bannon as an engrossing and enjoyable experience.

And yet, he told TIME, he was taken aback when Bannon began to argue that the current phase of history foreshadowed a massive new war. "I remember him saying, 'Well, look, you have the American revolution, and then you have the Civil War, which was bigger than the revolution. And you have the Second World War, which was bigger than the Civil War,'" Kaiser said. "He even wanted me to say that on camera, and I was not willing."

Howe, too, was struck by what he calls Bannon's "rather severe outlook on what our nation is going through." Bannon noted repeatedly on his radio show that "we're at war" with radical jihadis in places around the world. This is "a global existential war" that likely will become "a major shooting war in the Middle East again." War with China may also be looming, he has said. This conviction is central to the Breitbart mission, he explained in November 2015: "Our big belief, one of our central organizing principles at the site, is that we're at war."

To understand Steve Bannon, you have to understand what happened to his father. "I come from a blue collar, Irish-Catholic, pro-Kennedy, pro-union family of Democrats," he once told Bloomberg Businessweek. Martin Bannon began his career as an assistant splicer for a telephone company and toiled as a lineman. Rising into management, the elder Bannon carved out a comfortable middle-class life for his wife and five kids on his working man's salary. Friends say Steve pays frequent visits to his father, now 95 and widowed, at the old family home in Richmond's Ginter Park neighborhood.

The last financial crisis put a huge dent in Martin's life savings, according to two people close to the family. Steve watched with fury as his former Wall Street colleagues emerged virtually unscathed and scot-free–while America's once great middle class, the people like his father, absorbed the weight of the damage.

"The sharp change came, I think, in 2008," says Patrick McSweeney, a former chairman of the Republican Party of Virginia and longtime family friend. Bannon saw it as a matter of "fundamental unfairness": the hardworking folks like his father got stiffed. And the bankers got bailed out.

Until then, Bannon had been, as he later put it, "as hard-nosed a capitalist as you get." Born in 1953, Bannon was Student Government Association president at Virginia Tech, but as he explained in the 2015 interview with Bloomberg's Joshua Green, he wasn't particularly interested in politics until he enlisted in the Navy. "I wasn't political until I got into the service and saw how badly Jimmy Carter f-cked things up. I became a huge Reagan admirer," he said. "But what turned me against the whole Establishment was coming back from running companies in Asia in 2008 and seeing that Bush had f-cked up as badly as Carter. The whole country was a disaster."

After seven years as a Navy officer, Bannon had earned a master's degree in national-security studies from Georgetown, followed by an M.B.A. from Harvard. From there he went to Goldman Sachs, where he says he watched as the staid culture of a risk-averse partnership was transformed into a publicly traded casino, with the gamblers risking other people's money. He left the bank to form his own boutique firm in Beverly Hills, specializing in entertainment deals. At one point, he even dabbled in trading virtual goods for players of the video game World of Warcraft. His partner Scot Vorse told TIME that he was the nuts-and-bolts guy, while Bannon was the big outside-the-box thinker and the driving force. "It's all about aggressiveness," Vorse says. "Steve's not willing to take no for an answer. He's a sponge. He's very bright. He listens. And he's a strategic thinker, about three or four steps down the road."

The little firm won major clients, including Samsung, MGM and Italy's answer to Trump, the billionaire and future Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi. Bannon's biggest score, though, was not immediately apparent. In 1993, cable-television mogul Ted Turner bought Castle Rock Entertainment in a deal that Bannon helped deliver, and as Bannon has told the tale, at the last moment Turner insisted that the banker put some skin in the game. Instead of cash only, Bannon & Co. received a piece of five Castle Rock television shows–including a struggling sitcom called Seinfeld.

Meanwhile, Bannon was gradually evolving from dealmaker to filmmaker, with an unusual detour to manage a troubled experiment in the Arizona desert called Biosphere 2. In 1999, he served as co–executive producer of Titus, a star-studded adaptation of a Shakespeare play that went nowhere. Turning to documentaries that he wrote and directed himself, Bannon became a sort of Michael Moore of the right, with films celebrating Ronald Reagan, Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann.

Bachmann, a former member of Congress from Minnesota, says Bannon was able to see what the mainstream media either could not or would not. There was a rising tide of disgust in America, which the coastal elites dismissed in "a grotesque caricature of what Donald Trump has called the forgotten man," Bachmann says. "He was simply trying to give voice, I think, and give a platform to people who were not only being ignored but who were being lied about in the mainstream media."

Bannon's life became a crusade against political, financial and cultural elites of all stripes. Bannon's philosophical transformation showed in his clothes: no one could look at his preferred uniform of T-shirts, cargo shorts and stubble and think Goldman Sachs.

At Breitbart, Bannon was a volcanic figure, according to a number of former staff members who found themselves crossways with the boss. Republican consultant John Pudner, a Bannon friend who briefly worked at Breitbart as the editor of a sports section, recalls the time Bannon "reamed me out"–just hours before he turned around and connected his friend with a plum new job. "He could hit you with that level of intensity and at the same time be singing your praises," he said.

Not everyone is charitable. "He is legitimately one of the worst people I've ever dealt with," former Breitbart editor Ben Shapiro told TIME last year. "He regularly abuses people. He sees everything as a war. Every time he feels crossed, he makes it his business to destroy his opponent." The sentiment was echoed by conservative commentator Dana Loesch, a former Breitbart employee. "One of the worst people on God's green earth," she said on her radio show last year. Bannon was charged with domestic violence after a dispute with his ex-wife in 1996, though she declined to testify against him and the case was dropped. She later claimed in legal papers that Bannon had objected to a private school for their daughters because there were a lot of Jewish students attending and he didn't like the way they are raised to be "whiny brats." Bannon denied those claims, and declined through a White House spokesperson a request from TIME to comment for this story.

In Trump, Bannon found his ultimate outsider. He frequently had the candidate on his radio show, and former staffers say he ordered a steady stream of pro-Trump stories. Now Bannon's imprint can be seen on presidential decisions ranging from the hiring of former Breitbart staffers to key White House positions to the choice of Andrew Jackson's portrait–a Bannon idol–for display near the President's desk.

"Where Bannon is really having his instinct is on the policy front," says a longtime Trump ally. Which policies? "All of them. He's Trump's facilitator." In a Trump White House, this adviser says, you can only get–and keep–as much power as the President wants you to have. But Trump and Bannon "sat down before the election and made a list of things they wanted to do in office right away," says this adviser. Trump is the one deciding which items to tick off. "Bannon's just smart enough to give him the list."

However much the disruptive Trump may have welcomed the outrage of the ruling elites, the slash-and-burn style has caused real internal tension at the White House. Senior staff say Trump has instructed chief of staff Priebus to enforce more orderly lines of authority and communication from now on. Presidential counselor Conway has agreed to take an increased role in planning White House messaging with the policy and legal shops.

The internal tribulations of the past few weeks are a clear cause for worry. The decision to rush the refugee order through a relatively secret process came after Bannon and Miller noticed that documents circulated through the National Security Council's professional staff were leaking to the press, according to Administration sources. Bannon and Miller moved to curtail access to forthcoming memos and drafts. Members of Congress, and even some Cabinet members, were cut out of the loop or had their access sharply limited.

As a result, the sources said, after the controversial order was signed, confusion reigned. An unknown number of holders of green cards and valid visas were en route to the U.S. The initial White House guidance was that they should all be turned back. But as immigration and civil-liberties lawyers rushed to federal court to challenge the order, the White House reversed itself, saying green-card holders would be granted waivers. Reporters had difficulty finding out even basic facts, like the names of the countries from which travel was banned. Days later, the President even intervened to amend the order that appointed Bannon to a regular spot on the National Security Council. Trump wanted his CIA director, Mike Pompeo, there too.

By Tuesday night, four days after the order was issued, the White House was trying to project a normal tableau. Trump orchestrated a prime-time announcement of his first Supreme Court pick, conservative Colorado judge Neil Gorsuch. But if the Administration had finally struck a note of steadiness, it surely didn't mean that Bannon had been banished.

The President had, once again, provided a course correction. But his central populist message and methods, the one brought to life in conversations with Bannon, remained. In the fight for the forgotten people, disruption was not a bad thing–it just needed to be done with more forethought and follow-through.

That push and pull between demolishing the Establishment and leading it is likely to continue as long as Trump is in office. It's the contradiction facing every outsider who wakes up inside. The entire presidential campaign had been narrated by Trump as a clash between David and Goliath, notes one senior Administration official. But now David has become king. "David shot Goliath with a slingshot but didn't hold a press conference or sign an Executive Order. Not everything we do here has to move so quickly or be released so spectacularly."

–With reporting by ALEX ALTMAN, ELIZABETH DIAS, MICHAEL DUFFY, PHILIP ELLIOTT, ZEKE J. MILLER and MICHAEL SCHERER/WASHINGTON