10 April 2017

TRENDING

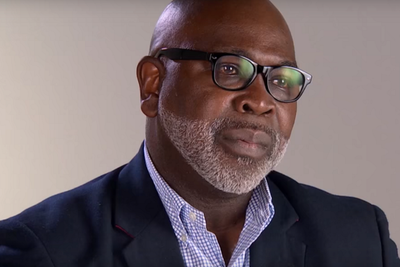

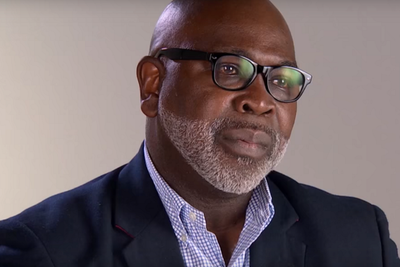

Those who believe in widespread access to abortion and contraception have for far too long ceded the moral high ground to anti-choicers, argues Deep South abortion provider Dr. Willie Parker in his new memoir, Life's Work: A Moral Argument for Choice. Women, families and the country have suffered as a result, he says.

A trained obstetrician, Parker refused for years to perform abortions, instead referring his patients to other physicians when the need arose. But after working at an outpatient clinic for indigent people in Hawaii in the early 2000s, and seeing what happened when that clinic stopped provided abortions, Parker was forced to reckon with his indifference. Inspired by a group of young residents who courageously took matters into their own hands, as well as Martin Luther King's final sermon, "I've Been to the Mountaintop," Parker decided his life course had to change.

Within two years, he had left his idyllic Hawaiian life to train full-time in abortion care and commit to Dr. King's version of justice. "On that day, I decided to exercise Christian compassion not by proxy, but with my own capable hands," Parker writes.

In his book, Parker – who now is board chair for the group Physicians for Reproductive Health and provides abortions at the last remaining clinic in Mississippi – delves into his religious upbringing in Alabama as well as the love of science and medicine that took him to Kentucky, Iowa, Michigan and Washington, D.C.. Parker makes a humanistic case for easy access to abortion, and says the Christian thing to do is help women in need, without judgment.

Parker recently spoke to Rolling Stone about Life's Work, his decision to start providing abortions in the South and the moral fallacies of the anti-choice movement.

How did this career path open up for you?I was working at a clinic with six women who were in their first year of residency, when we had an administrator sort of unilaterally decide that we'd no longer provide abortion services – something that in Hawaii does not bear the same stigma as on the mainland, and something that has been available in the state since 1970, before Roe. This administrator, under his conviction of interpreting regulations very conservatively, decided that abortions would put the funding for other programs at risk, and it was convenient that for him as a born-again, fundamentalist Christian, it was consistent with his values. These six women who were in the earliest part of their training, who should have been by all conventions more concerned about just making it through their program, had a sense of kinship and solidarity with poor women that they saw in their clinic. They decided it was unjust to take away their access from them, and they formed a clinic on their own.

At that point, I was sympathetic, but not compassionately moved to the point of being an abortion provider. Even though I wasn't providing abortions, I felt deeply this was a service my patients needed to have. That, combined with the residents' exemplary behavior, brought me to the crisis moment – where that sermon by Dr. King was instrumental in me examining my role in addressing injustice and oppression. Their modeling principles of compassionate behavior, for me, was very consistent with lessons of deeper humanity that have been given to me by all kinds of people, but in particular from women. As they exercised their agency, it called me to a deeper humanity. I found myself more willing to be defined by how I respond to injustice than about accommodating customs and norms that are rooted in injustice.

You write about Martin Luther King's religious teachings as your touchstone texts, but also about the importance of Malcolm X, among others. How did they influential to you?

Their sense of work is from a deep place of humanity and wanting for others what you want for yourself. The courage that's necessary to assert yourself on behalf of human dignity, they modeled that for me, despite risk. And that became very important for me, because entering my role as an advocate for women's reproductive rights and basic human equality across gender, I was well aware what happens when you go against convention and dogma and custom. There was no naiveté. There was just an assertion of my responsibility to pursue justice and human dignity. They modeled that for me, and I took courage and took note. While if you skim the surface of their writing, you think they were coming from completely different places, but they were complementary pieces of the same quest for justice. I see this work that I do, although in a different context, as no different from the work they did. They were working on civil rights and racial justice; I'm working for gender justice and human equality for women. The luxury I have is that their writing and their life examples informed me, but they didn't have someone like themselves to inform their path.

You write that you're descended from slaves and how that informs your beliefs about bodily autonomy as it relates to abortion access. Tell me about connecting those dots.

Because we're so uncomfortable with the issue of race in our country, and particularly our racial history, any reference or analogies to slavery sound like bombast to someone who doesn't want to explore that history. It's not bombastic in terms of a man in a patriarchal world and society. Most men, particularly if you're not a person of color, won't have any frame of reference of what it's like to have their life chances determined by someone else. As humans, we span equal in our humanity, and yet through slavery and the ugly legacy thereof, human beings were able to own and control other human beings. Women are born into that sort of subservience and ownership because patriarchy rules the day. Women are devalued because they are not male. I don't know what that's like from a gender standpoint, but I have lived in situations where my life circumstances were determined by somebody else, even though I haven't lived under slavery. There has still been economic and racial discrimination that has the potential to limit my trajectory. I don't think it's bombast at all that the closest thing I could think of that would be analogous to women not being in control of their reproductive rights would be the horrible legacy of slavery we have in this country.You also write about the importance of advocacy in every state, regardless of the red or blue tinge – because once one "class" of women is deemed unworthy of the procedure, then eventually all will be.

One of the things I'm clear about is that for women, even when they're economically stratified or racially stratified, in a patriarchal world and society, they are all vulnerable. The system works against even the most powerful women in a patriarchal society. Even powerful women can be constrained by the aspirations of the most ordinary, mediocre men. I think you saw that in the last election: One of the most prepared candidates, with experience and a track record in government and service, her interests were subordinated to the fact that people were not comfortable with a woman being in the most powerful position in this country, and by default the world. When women fail to recognize the things that give them sorority – and that is their almost inability to escape their subordination through patriarchy – it only stands to reason that women have to realize that unless all of them are free, none of them are. That's the notion of building solidarity across race. That's the concept of intersectional analysis that is core to reproductive justice, which is what I subscribe to.

In one chapter of your book, you plainly lay out how an abortion is performed. I'm not sure many people know exactly what happens during the medical procedure. But you've done thousands, and detail exactly what goes on in the room. Why did you decide to include that section?

My rationale is: The truth will do. I think we've empowered people opposed to abortion by being mute or defensive about the biological realities of pregnancy termination. We've allowed them to create a narrative that is patently false, and yet, without any competing narrative, it bares a truth that doesn't exist within it. I think people are able to handle the truth. The numbers show that most people can conceptualize pregnancy termination in some form or another. Many people approve of abortion. Even if they don't approve of it in all cases, they can certainly understand where it might be necessary. I think if we're going to shift the culture around this very important service, we've got to trust people that they are capable of dealing with the substance of it, and maybe developing the compassion to handle the nuance. I'm not a big fan of euphemisms, because at the end of the day, whatever we call it, we're doing it. If we're going to have honest disagreements, we have to put facts in the arena.

Six months ago, Democrats had ending the Hyde Amendment in their national platform, and now the global gag rule is back in place under President Trump. But it's state-level policies that have the more immediate impact on your patients. Do you worry about state legislators being emboldened under this administration?

I don't worry about it – I expect it. Roehas remained in place for 44 years, which has meant that the long-term strategy of those opposed to abortion came to understand what liberals don't understand: that a sustained political engagement at every level was critical to them shifting the ground. Conservative folk don't vote every four years – they vote in every political cycle. They vote at every level, which is why you have the Tea Party in 2010 as a direct response to having a black president. This whole notion of "taking our country back" – that rhetoric had never been spoken in the same way before the president was black. At every level, people understood to get engaged politically. So you have statehouses that slipped in 2010, governorships that went from liberal and progressive to conservative. That sustained engagement meant a very vocal, organized, well-funded, numerical minority of the Republican Party swept statehouses. You're right on point: Local politics are what makes a difference. Getting people engaged in a sustainable way at the local level, all the way up to the federal level, is what's going to help us to stem this tide. It can't be every four years.

One final piece of the book I'd like to talk about is the shortest chapter, and I would venture the angriest – the one on the cynical "black genocide" movement. Why did you choose to address this conspiracy theory, pushed by anti-choice activists, that abortion is a white plot to kill black babies?I would say it's a righteously indignant chapter. I think it really touches in an intersectional way on why you would frame abortion as a "black genocide" issue. To cry "black genocide" would be to foster a sense of racial paranoia and vulnerability among black folk. If you look at the fact that the same people who declare they are "pro-life" and insist poor women and women of color continue their unplanned pregnancies that they didn't want, those are the same people who do away with the very resources that would be necessary to be a parent and raise that child with a modicum of human dignity. You can't have it both ways. The same people are opposed to housing, education, health care, while they advocate for black women to have black babies – but at the same time wax strongly anti-immigrant, and they're strongly anti-non-Christian, all things that are reflective of the shifting demographics of this country. By 2050, we'll be a nation of minorities, because no group will be greater than 50 percent of the population. So you have people who are opposing the very things that make up this country as it is now wanting to return to some notion of "making America great again" – which means "making America white again." It just makes sense to me that the people opposed to abortion are really interested in controlling the fertility of white women. Because white women are the ones who are working outside the home and defying conventional nuclear family concepts. They've been able to do that by gaining control over their fertility. So what they understand is that if they exploit the fact that we're very uncomfortable with race in this country, and frame the opposition to abortion as one of anti-racism – that if they can stop abortion for black women, they can stop abortion for all women. This is their primary interest. The only person who can have white babies is a white woman. And yet, if ultimately controlling the fertility of white women – who have been the greatest benefactors of affirmative action in terms of having aspirations outside the nuclear family – then all these other policies make perfect sense. But they don't make any sense unless you can follow the thread and connect the dots to realize that they're hoping to control the fertility of more than just black women.

This interview by Caitlin Cruz which appeared in Rolling Stone on April 10, 2017 has been edited for length and clarity.

###

April 11, 201